Home

JD Features:

A Printer Looks at Fingerprints

By Fred Woodworth*

SOMEDAY, evidence could determine your fate in a court of law.

Now pause for a moment and consider that last statement: Is it true? "Well," you say, "I'm not planning on committing any crimes -- not serious ones, anyway. But I suppose it's conceivable that I could be charged with something whether I did it or not, and in the current climate of 'zero tolerance' and extreme profitability to police agencies in seizing property and sending people to jail, it could happen. So the statement is true; evidence could determine my fate in a court of law."

Wrong! Evidence doesn't determine anything; PEOPLE who INTERPRET evidence call the shots. While this may seem like a nitpicking distinction, it is crucial to the understanding of how "legal" rights have gone far toward vanishing in an area you may not have thought much about.

To an increasing degree, evidence is an abstraction far removed from the normal experience of the human beings who comprise juries. Thus the jury system, like all other aspects of statism, has migrated toward even further authoritarianism -- in this case toward the reliance on the unseen, the indecipherable, or the incomprehensible, as delivered as fact by "expert witnesses". Consider for an example of this, reliance on DNA "evidence", which is growing by leaps and bounds: no one can see DNA directly; the molecules are so tiny that they are smaller than the wave-forms or graininess of fight itself, so they are in principle invisible. In order to "see" them, you have to bombard them with electrons or other subatomic particles, or "observe" or test them by other indirect means. Such evidence as that involving DNA is purely a matter of announcement of conclusion by laboratory workers. Recent alleged developments, however, permit the finding and analysis of DNA on all kinds of handled objects: coffee mugs, pens, keys, gloves, doorknobs, etc. Soon it may be "possible" to "detect" DNA particles adhering to air molecules as a result of those molecules' contact with a person's lungs.

This is profoundly troubling, because it involves judgments by privileged elites, that are merely sent for blind ratification to the jurors who provide a socially acceptable facade. The already grave authoritarianism of the judicial system thus becomes quietly displaced by one in which ordinary people are puppets dancing on the strings of those who profess to see unusual things hidden from all view but theirs. In short, you have to take their word for it, and in a society that is shot through with propaganda to induce reverence toward authority figures, extremely large numbers of people will indeed blindly take their word.

Even where no malicious intent is present, so-called experts are prone to errors or the subconscious slanting of their own views due to preconceptions on their part, or subtle cues emanating from others. A classic instance of error induced by experts themselves, who didn't realize they were doing it, was the case of Clever Hans, a supposedly learned horse belonging to a Mr. von Osten, in Germany around 1900. Robert Rosenthal, of Harvard University, has briefly outlined the matter this way:

"Hans gave every evidence of being able to add and subtract, multiply and divide... He was also able to read and spell, to identify musical tones, and to state the relationship of tones to one another. His preferred mode of communication... was by means of converting all answers into a number and tapping out these numbers with his foot.

"...No...signals could be observed to control Hans's tapping responses. In fact, on Sept. 12,1904, thirteen men risked their professional reputations by certifying that Hans was receiving no intentional cues from his owner or from any other questioner.

"The investigation of Hans's abilities is a classic ... First [the investigator] established that Hans was, in fact, clever, and that his cleverness did not depend on the presence of his master. Almost anyone could put a question to Hans, and the chances were good that an accurate answer would be forthcoming. The experimental addition of blinders reduced Hans's cleverness. [And when] questioners asked questions to which they did not know the answers, ...Hans's accuracy diminished."

Eventually it was discovered that extremely slight unconscious cues given off by ordinary people were reflected in the "answers" of the horse; and an experimenter in fact learned how to "read" people in this manner himself. The case has enormous significance in light of recent use by police of "drug dogs" to locate alleged contraband -- which at times consists of residues so faint that they may well be imaginary - and many arrests appear to be based on "probable cause" that reduces down to "evidence" no different from that in the Clever Hans case.

ORDINARILY, people think of fingerprint evidence as exact, scientific, unmistakable, verifiable. Such evidence rests, supposedly, on the statistical reality that it is highly unlikely for any two individuals to have exactly the same prints. Therefore, if I am to show that fingerprint evidence is not necessarily all that it's painted as being, I have to assure you that I am not claiming that people here or there exist who have fingerprints identical to each other. (For all anyone knows, there may really be some such persons, but, again, the odds are tremendously against it.)

However, it is difficult to define what is meant by "identical". Due to the nature of the surfaces printed onto, as well as the elastic (flesh) surfaces that impart the prints, considerable variation in the print from any particular finger is to be expected. For this reason, as well as the fact that some persons' prints may actually be very similar to each other, the likelihood of existence of virtually indistinguishable prints shoots far past the smiling picture of statistical certitude drawn by the propagandists for fingerprint identification.

Beyond this, the unlikelihood of identicality is based on sets of ten fingerprints -- and while a full set was originally required in courtroom evidence, increasingly today we find that a single print is being regarded as conclusive. This boosts the possibility of similarity even more. (Note that banks and driver's license bureaus which people are forced to deal with are requiring but a single print -- not all ten.) Single prints, usually of the right index finger or thumb, are being used currently to check the identity of persons applying for jobs, seeking certification as day-care workers, tow-truck drivers, or nursing-home staff. These send millions of prints into the identification system, and false matches are becoming common. Further downgrading the supposed exactitude of fingerprint identification is the surprising fact that some people have no fingerprints (friction ridges) at all: according to Jim Wayman, director of the National Biometric Test Center at San Jose, one out of 50 people -- not one out of a billion, not one out of a million, or one out of a thousand, but one out of FIFTY - has smooth fingers with no friction ridges, or with ones that are all but absent.

In case you're still confident that most people nonetheless do have quite clear prints, which are obviously distinct from one another, ponder these words from a fingerprint textbook:

"How to compare fingerprints: What factors must be present for one to declare that two prints were made by the same finger?

"The court and jury are usually not familiar with fingerprint evidence, and must of necessity rely upon the honest judgment of the witness. As a law enforcement officer, it is your obligation first to convince yourself that two prints are identical before you testify to that fact in court. "

Think about this. You must "convince yourself." Let's say you were being asked to compare two numbers in a logarithmic table, say 3.91202, and 3.93183. You either see and understand, and KNOW, that they are different, or you don't; but there is no matter of "convincing yourself". Quite clearly, fingerprint identification is by no means as cut-and-dried as recognition of mathematical identity. The text goes on:

"As you know, many latent impressions are worthless smudges, while many are clear, easily identified prints. Between these two extremes will be prints whose clarity, or lack of it, makes a positive pronouncement of identity difficult. When such an impression comes up for identification, unless you are sure in your own mind beyond a reasonable doubt..., then by all means do not testify to their 'identity."

Right here is where the "science" of fingerprint identification seems to pass into the realm of Clever Hans subjectivity. It would be hard, if not impossible, for a fingerprint "expert" who believed totally in the identity of two prints (as a result of other factors, including bias or persuasion), to refrain from slanting his own mental picture of the prints and their alleged similarity.

"If the fingerprint technician should look at the known print before the unknown one, he is bound to be influenced, whether he realizes it or not, by the ridge formations in it. ... He may unconsciously see in the unknown print formations which were clearly visible in the inked print but which may not be clear in the latent impression. We do not mean to infer [sic] that he would do this with any dishonest intention. It is just human nature to do so, and may even occur without the technician's knowledge."

It's looking less and less scientifically exact, is it not?

"Many experts won't take a case into court with less than twelve characteristics" [print similarities] "but there are many cases on record in which convictions have been obtained with eight to ten. There have been cases in which the jury accepted as conclusive proof an expert's opinion with only six ridge characteristics showing... "

BIOMETRICS -- the branch of anthropology concerned with measurement of the human body - was the forerunner of fingerprint studies, but, strangely enough, measurement is not of much use in the comparison and classification of fingerprints. Instead, the study of these patterns focuses on the particular ways in which the ridges of skin whorl or loop or arch around each other. Elastic deformation -- the tendency of a pliant surface to bulge or stretch according to the amount of pressure on it -- results in variant prints from any particular finger. More skin surface, or less; fewer friction ridge characteristics, or more, will result as the touch of a finger exerts varying force against the surface that will eventually exhibit the fingerprint. Excessive force of touch may reveal more of the detail toward the sides of the finger while obscuring that of the middle.

And, at this point, the mechanics of transfer of finger prints exhibits much in common with ordinary printing, as of ink on paper.

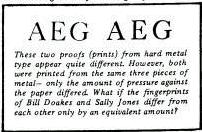

In the classic, original technique of book printing (known as letterpress), metal type having a relief surface was contacted by an ink-bearing surface, usually a roller. As the image portion or face of the type took on ink, paper pressed against this type subsequently was left with a printed image on it. Type, however, unlike the friction ridges and flesh of fingers, deforms very little under pressure. Nevertheless, even type -- metal type -- is capable of delivering a vastly differing impression under differing conditions of pressure and on hard or soft papers. A typeface that looks spindly and weak if printed on a smooth-surfaced paper may look robust and bold when printed with much greater pressure on a spongier surface. Indeed, it might be difficult even to say with certainty whether two separate images were produced from the exact same piece of type.

As years went by, various means of printing more rapidly and conveniently were introduced, and some of these involved the transfer of images in ink, not from metal type, but from metal, rubber, or plastic plates or surfaces. Here we begin to approximate more closely the curved and/or flexible printing surface of skin, and here too we run into the tremendously equivocal nature of the image when it is printed from a soft plate, onto a soft paper, with varying amounts of pressure. Now it becomes almost impossible even for an expert typographer to Identify a typeface, or to tell the difference between two typefaces, when the printing has been done under less than ideal conditions or by unskilled or careless pressmen.

Fingerprints, you will note, are almost never set down at some crime scene under any BUT poor conditions or in any other way than extremely carelessly.

In commercial printing, even with presses explicitly designed to deliver the best possible impressions from the most carefully made plates, fairly great quantities of wasted sheets are produced as a print run is gotten underway. Blurry, smudgy, under-inked or over-inked copies emerge from the press for some time before all the factors settle down into the proper balance of ink film, transfer pressures, and temperature. Fingerprints, meanwhile, produced haphazardly with no equipment whatsoever and with no attention paid to exerting proper pressures, are popularly supposed to be models of clarity that detectives can photograph and compare as if they were variant texts of a book. In reality, obviously, the proportion of the "prints whose lack of clarity makes a positive pronouncement of identity difficult," must be rather great. In fact it seems likely that this would be the overwhelming majority of prints, and that far more instances of police identification of prints are really statements of probability, than anything approaching certainty. They are opinions.

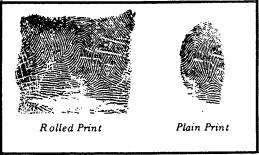

A FURTHER DEPARTURE from truly scientific accuracy comes with the comparison of fundamentally dissimilar samples. Formal fingerprinting, as done to persons in custody or to those who for one reason or another voluntarily submit to the procedure, consists of taking rolled prints -- ones in which the entire friction-ridge surface of the end joint of the finger is rolled to create a complete print. Obviously, fingerprints inadvertently left at some scene will seldom, if ever, reveal all of the same features. A serious but never discussed implication is buried in these facts; and that is that while every human being's prints may well be different from every other's, surely there are bound to be certain sections that are identical -- and the comparing of some small portion of a print by person X with a large number of full portions in rolled prints of many other persons, may well result in a mismatch. This is reducible to a mathematical formula, which can be stated in language as: The smaller the sample that is compared to a primary object, the greater likelihood there is of a correspondence.

An illustration of this principle can be made by supposing that some play of Shakespeare be compared against the present issue of The Match, in its totality. Obviously they will be entirely dissimilar. Now compare some isolated short sentence from this journal to every sentence in Shakespeare: there may or may not be two that are exactly the same, but at least the odds will now be tremendously greater in favor of a correspondence. Finally, if you selected some pair of words and then hunted all through the Bard's work for them, odds would approach 85% or higher that you'd find that identical couple. At a single word the odds would rise still farther, and at individual letters of the alphabet the odds would, of course, be precisely 100%.

S0 FAR, in this discussion, I've been willing to assume that persons comparing fingerprints were merely hampered in giving precise, true answers about identity, by the somewhat equivocal nature of fingerprints themselves. I've assumed that those persons, usually police, were individuals of honesty and goodwill, and that any errors were only the ones that anybody might make. However, my views are considerably at variance with such a naive belief, and now it is time to ask: Can fingerprint evidence be deliberately distorted or contrived in order to show an identity where there is none -- or, in other words, to produce "evidence" that will allow conviction of an innocent person?

The answer to this is an emphatic Yes. For all the reasons heretofore outlined, there is much room for latitude of interpretation in some cases about some prints. Furthermore, it is entirely possible for fingerprints to be manufactured, or left at some scene that a defendant never visited, and this is an opinion that I back up with 27 years of experience in graphic arts and printing-related study. Transference of actual prints made by real fingers, from one location to another by means of sticky tape, is one possibility, with techniques long known to law enforcement officers. However, I am here concerned with the actual reproduction of prints, by mechanical or photomechanical means.

Can a fingerprint be reproduced? Of course it can -- at left, below, you see such a reproduction, a print, in ink, on paper. A printing plate, carefully enough made, can easily contain far more detail than necessary to duplicate the print from a human finger. Compared to the amount of detail in a halftone plate for printing a photograph, for instance, where the plate must hold information on about 40,000 dots per square inch, the reproduction of a fingerprint is a relatively trivial matter.

Nor does it involve carrying a printing press to some crime scene and printing someone's print on a window-ledge there in order to implicate him or her. Instead, it could be done by a contrivance like a tiny rubber stamp.

The possession by anyone of your fingerprints opens the door to such a possibility. How many times this may have been done in the past is something we will never know, but there are certainly evidences of it. Clifford Skeete, formerly a criminologist with the Inglewood California police department, became a fugitive in 1990 when a report concluded that he had manufactured evidence against a suspect by superimposing a fingerprint onto a murder weapon. What method he used has not been revealed, but in this instance the deception was discovered before trial, and officials were reluctantly re-examining all other cases he had handled.

R. Austin Freeman, a chief surgeon in the throat and ear department of Middlesex Hospital, London around the 1890's, later became the Deputy Medical Officer of Hollaway Prison in London - and later, when his health broke down, he turned to writing. His first novel appeared in 1907 and used a plot device that he'd obviously been turning over and over in his mind through his medical experience in the hospital and prison: the forging of a fingerprint. Unfortunately I've been unable to locate this novel, so do not know what method he had decided was workable; but I cite this instance to show that some minds have been pondering such possibilities for a long time.

Modern plastic materials probably provide the widest array of possible substitutes for authentic fingers and friction-ridges that ever existed. Photo rubber plates for printing use, for example, now may be obtained in a variety of hardnesses (or softnesses), some of which are practically indistinguishable from that of flesh. Anyone with access to a set of black-and-white fingerprints of some person could without much trouble arrange to have negatives made, from which photographic rubber copies would be exposed and developed. Pressing such copies against an inked flat surface and then "touching" some object with them would result in an inky fingerprint on that object. If instead of ink one used skin oils or any of the other substances that commonly appear in real fingerprints, such as blood, paint, motor oil, etc., the resulting print would be indistinguishable from that left by the original human hand.

WHETHER or not you believe that fingerprint evidence may be as fallible as I've suggested, I hope that this brief criticism has at least introduced a doubt about ANY statements that must be taken on faith. The journey of ten thousand miles does indeed begin with a single step; and the effort to build a free world in some far distant future begins here and now with the first brick: mistrust of, and skepticism toward, every tenet, principle, action, procedure, policy, or justification of coercive authority. (1997)

Headline in The New York Times, April 7, 2001: FINGERPRINTING'S RELIABILITY DRAWS GROWING COURT CHALLENGES "...In courts around the nation, defense lawyers are using evidence of fingerprinting's fallibility to get it declared inadmissible under standards set by the Supreme Court to keep unproven 'junk science' out of courtrooms."

* Mr. Woodworth is a writer and printer living in Tucson, Arizona. This article appeared in a publication edited by Mr. Woodworth: The Mystery and Adventure Series Review, No. 34, Summer 2001. The address is The Mystery and Adventure Series Review, PO Box 3012, Tucson, AZ 85702.

© Justice Denied