Possibility

Of Guilt Replaces

Proof Beyond A Reasonable Doubt

Las Vegas Detectives, Prosecutors And Judge Orchestrate Kirstin Blaise

Lobato’s Serial Rape By The Legal System

By Hans Sherrer

Justice:Denied

magazine, Issue 34, Fall 2006, pp. 24-34

On the hot, arid evening of Sunday, July 8, 2001, a man was

‘dumpster diving’ in a trash enclosure several

blocks west of the Las Vegas strip. Around twilight he lifted a trash

covered piece of cardboard next to the dumpster and saw a

man’s torso. He called 911.

Police

at crime scene

The first police officers arrived at 10:36 p.m. One of the officers

went inside the trash enclosure and saw a human foot exposed with the

rest of the person’s body buried under a pile of trash. He

also saw still moist bloody shoeprints leading away from the body

toward the trash enclosure’s opening.

After medical personnel arrived, one of them lifted the trash covered

cardboard and determined the body was that of a dead man.

Several crime scene analysts arrived and they began systematically

removing piece by piece the large number of trash items covering the

body. Only a few items were collected as evidence, while the rest of

the evidence was discarded. When the body was fully uncovered it was

apparent that the man had many wounds, including an amputated penis.

It appeared that the man had been living in the trash enclosure.

It wasn’t until 3:50 a.m. on Monday the 9th, that the

coroner’s investigator examined the body at the scene. At 8

p.m. that night the FBI identified the dead man as Duran Bailey from

his fingerprints.

When the man who found Bailey’s body was questioned, he said

he hadn’t stepped in Bailey’s blood, which was

completely covered by trash. His shoes were examined and there was no

blood on their soles.

Autopsy

determines

Bailey’s cause of death was “blunt head

trauma”

Clark County Chief Medical Examiner Lary Simms performed

Bailey’s autopsy. He found that while alive, Bailey

experienced a plethora of serious injuries to his neck, face, head and

upper body, including defensive wounds to his arms and right hand.

Simms also determined that following Bailey’s death he was

stabbed several times in his abdomen, his penis was severed at its

base, and his anus area was stabbed and sliced. Simms determined

Bailey’s cause of death was “blunt head

trauma,” and “a significant contributing condition

was multiple stab and incised wounds,” including a severed

carotid artery. 1

A month after Bailey’s autopsy, Simms expressed his opinion

during a preliminary hearing for the person charged with

Bailey’s murder that it was “more likely than

not” his death occurred within 12 hours from when the first

officer arrived at the scene – or no earlier than 10:36 a.m.

on Sunday, July 8. 2

Non-investigation

of prime

suspects

Las Vegas Metro PD (LVMPD) Homicide Detectives Thomas Thowsen and Jim

LaRochelle were assigned to investigate the case.

Thowsen and LaRochelle immediately had a prime suspect. While the crime

scene was still being processed on the morning of July 9, a woman named

Diann Parker approached one of the police officers and told him,

‘I might know who that guy is. I was the victim of a rape a

week ago and that might be the guy that did it.’ The

information was relayed to the detectives.

The detectives went to Parker’s apartment on the 9th to

informally question her. She told them that Bailey and her were

acquaintances, and that she had on occasion exchanged sex with him for

crack cocaine that he bought.

During their conversation Parker said that several

“Mexican” men in her apartment complex saw Bailey

slap and threaten her on July 1 while she was drinking beer with them.

The Mexicans talked with Bailey and told him to leave Parker alone.

When she left, they were “watching” to make sure

she got back to her apartment safely. Later that day Bailey returned.

He became enraged when she told him she didn’t want anything

more to do with him. After forcing his way into her apartment he beat

and kicked her, and raped and tried to sodomize her while holding a

knife to her neck and throat and threatening to kill her.

Afraid to go to the police because of Bailey’s threats, she

did call 911 three days later when he returned and tried to break into

her apartment.

She told the officer who responded that reporting Bailey’s

assault and rape of her was going “to get me

killed.” She also told the police, “If you all

don’t catch him, I will be dead.” 3

When she asked

the officer for protection he told her, “you got to do what

you got to do to protect yourself the best you can.” 4

She

was reluctant to give him too much information about the Mexicans

because she thought they could have been in the country illegally.

Parker also told the officer the homeless Bailey “stayed

behind the … Nevada State Bank” at

“Flamingo and Arville.” That is where

Bailey’s body was found three days later.

Parker told Thowsen the two apartment numbers where the Mexicans lived.

He talked with the apartment complex’s manager and learned

the names they used to rent the apartments. The manager also told

Thowsen they didn’t cause any trouble. Thowsen ran a criminal

background check on the names. No record showed up for any of them so

he did not interview the Mexicans.

Thowsen and LaRochelle not only knew that Parker had a significant

motive to want to see Bailey harmed or killed, but the photographs of

her extensive injuries from the beating Bailey inflicted and his knife

wielding were eerily similar to the wounds about Bailey’s

face and neck. Bailey even cut her neck with the knife near her carotid

artery, just as he was cut days later by his murderer(s).

In spite of the strong circumstantial evidence suggesting Parker and/or

the Mexicans may have been were involved in Bailey’s murder,

the detectives didn’t pursue investigating them by

interrogations or obtaining warrants to search their apartments and

vehicles to look for the murder weapon(s), bloody shoes or clothing, or

any other possibly incriminating physical evidence that could link them

to the crime.

When asked later why on July 9 he didn’t interview the

Mexicans after talking with Parker, Thowsen said words to the effect,

‘It was a long day and we were getting tired and at some

point you just have to call it a day.’

Laura

Johnson provides detective

with “third-hand” tip about Las Vegas stabbing

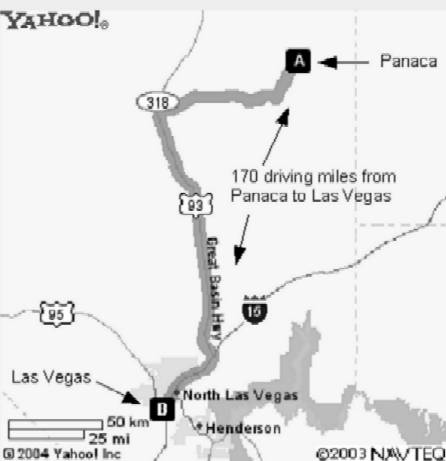

On July 20, twelve days after Bailey’s death, Thowsen

received a phone call from Laura Johnson, the juvenile probation

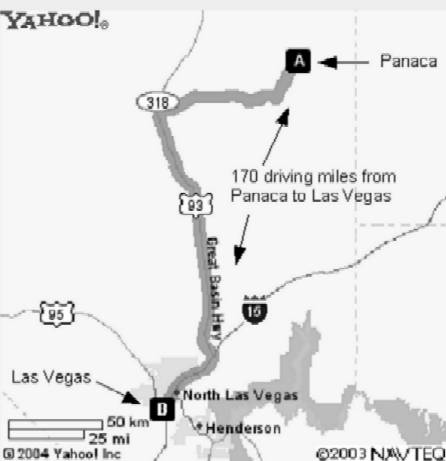

officer for Lincoln County, Nevada. Johnson’s office was in

the county seat of Pioche – more than 170 miles north of Las

Vegas. Johnson informed Thowsen that Dixie Tienken, a Lincoln County

teacher, told her that a former student of Dixie’s told Dixie

that she had cut off the penis of a man who attacked her in Las Vegas.

Johnson told Thowsen that the young woman’s name was Kirstin

Blaise Lobato, and she was living with her parents in Panaca, a small

town about ten miles southeast of Pioche. (Kirstin goes by, and is

known by her middle name, so this article will refer to her as

“Blaise”.) Johnson also told Thowsen she checked

and learned that Blaise owned a red 1984 Pontiac Fiero with a custom

license plate. She also said she had a Lincoln County sheriff deputy

drive by the home of Blaise’s parents and her car was parked

in front on the public street.

Thowsen ran a background check on Blaise after talking with Johnson. He

learned she was 18, and when she was 6-years-old her mother’s

boyfriend had sexually assaulted her for nine months in Las Vegas.

Detectives

Thowsen and LaRochelle

travel to Lincoln County to arrest Blaise

Thowsen arranged for LaRochelle and crime scene analyst Maria Thomas to

travel to Lincoln County, and he called the county sheriff’s

office to notify them the three would be arriving that afternoon.

Thomas was told that she would be impounding a car –

Blaise’s Fiero.

Within an hour or so after receiving Johnson’s phone call,

Thowsen, LaRochelle and the crime scene analyst headed north on US Hwy

93 in two vehicles to arrest Blaise for Bailey’s murder.

Johnson’s

statement to

Thowsen and LaRochelle

After the nearly three hour drive to Pioche, Johnson gave a taped

interview to the detectives. She reiterated what she told Thowsen on

the phone. However, she added that the detectives shouldn’t

contact Dixie – the source of Johnson’s third-hand

information about what Blaise had allegedly told Dixie –

because she thought Dixie would warn Blaise that they were coming to

arrest her.

Compounding Johnson’s implicating of Blaise in

Bailey’s murder without any personal knowledge of anything

Blaise said, or what she did or didn’t do in Las Vegas, was

the fact that Johnson made the false declaration in her statement that

Blaise had been in trouble with the law in Lincoln County and sentenced

to probation with Johnson supervising her. 5

However, the detectives

didn’t know Johnson made-up that inflammatory assertion,

because they didn’t verify her claims before deciding Blaise

was Bailey’s murderer. 6

After arranging for a Lincoln County sheriff deputy to accompany them

to where Blaise was living, and arranging for a flat-bed tow truck to

transport her car to Las Vegas, Thowsen and his colleagues headed to

nearby Panaca to arrest Blaise.

Detectives

unaware the incident

Dixie told Johnson about wasn’t Bailey’s murder

What Thowsen and LaRochelle didn’t know before forming their

opinions about Blaise’s guilt, was that the incident Blaise

told Dixie about was an attempted rape that she fended off with a knife

six weeks prior to Bailey’s murder. Shortly after midnight on

or about May 25, a “really big” black man over 6'

and 200 pounds grabbed the 5'-7" and 100 pound Blaise as she got out of

her car at the Budget Suites motel near Sam’s Town casino on

Vegas’ east side. He threw her onto the ground and as he

knelt over her with his pants pulled down, she pulled out a butterfly

knife her dad gave her for self-protection and tried to stab or cut his

groin area. She was able to get away from him, and she heard him crying

and saw him getting up as she drove off. 7

If the detectives had conducted even a perfunctory investigation into

the details of what Blaise told Dixie, they would have learned that

prior to Bailey’s murder Blaise had told multiple people

about the attack on her that occurred just before the Memorial Day

weekend – eight miles from where Bailey was later murdered on

Vegas’ west side. 8

They also would have learned from

investigating that at least ten people would swear they saw Blaise in

Panaca on July 8 at times from very early in the morning, to throughout

the day, to late that evening. The detectives also would have

discovered much more evidence, including medical and telephone records,

that excluded Blaise from even cursory suspicion of being involved in

Bailey’s murder.

However, the detectives didn’t have any idea they were

targeting the wrong person because they decided to arrest Blaise

without conducting an investigation into the substance of

Johnson’s conversation with Dixie.

Blaise’s July 20, 2001 interrogation

When the detectives arrived at the home of Blaise’s parents,

Larry and Becky Lobato, Blaise was in the shower and they were let in

by her younger sister Ashley. Neither of her parents were home. The

first thing Thowsen said to Blaise when he began questioning her at

5:55 p.m., was they knew she had been sexually molested by her

mother’s boyfriend when she was a child. Blaise began sobbing

and continued to do so, even after she signed a Miranda waiver 12

minutes later at 6:07 p.m., which was when Thowsen turned his tape

recorder on.

Blaise thought they were interrogating her about the Budget Suites

assault in May, because at no time before or after the tape recording

began did Thowsen or LaRochelle tell Blaise they were investigating the

murder of a man who had been savagely beaten and sexually mutilated,

its location in Las Vegas, or the day it happened. Consequently, she

had no way of knowing the details of the May assault she told the

detectives about bore no relationship whatsoever to the circumstances

or details of Bailey’s death six weeks later on July 8. There

are 16 significant details in Blaise’s 26-minute recorded

statement inconsistent with specific details of Bailey’s

death that Thowsen and LaRochelle would have known at the time of her

interrogation. There are eight additional significant details in her

statement inconsistent with the details of Bailey’s death

that the detectives would have been aware of shortly after her arrest,

due to forensic testing, expert evidence analysis, or subsequent

witness interviews. 9

No

matching points between

Bailey’s murder and Blaise’s statement

That Bailey, and Blaise’s assailant were black, both events

occurred in Las Vegas, and a cutting instrument was involved, were the

only three general areas of intersection between the undisputed

circumstances of Bailey’s death and Blaise’s

statement. However, those didn’t remotely

“match,” because Bailey was a smaller man

– shorter and much lighter than Blaise’s assailant;

Bailey was killed eight miles west of where Blaise was assaulted; and

Blaise only described attempting to cut her assailant once to get free

and flee, while Bailey was beaten severely, and stabbed and cut many

times before being sexually dismembered.

Thus there are no actual matching points between Blaise’s

statement and the details of Bailey’s death. The logical

explanation for the dissimilarity is because they were different events.

Blaise’s

arrest

True to the detective’s purpose of traveling to Panaca to

arrest Blaise on the basis of Johnson’s third-hand

“double hearsay” information – the

detectives abruptly terminated Blaise’s interrogation after

she told them she had been attacked “over a month

ago,” and placed her under arrest for Bailey’s

murder. Her car was loaded on the flatbed tow truck to be taken for

examination by the LVMPD Crime Lab.

She was booked into the Clark County Detention Center that night and

three days later (7-23) she was charged with, “murder with

use of a deadly weapon.” 10

Three days later the DA added the

charge of “sexual penetration of a dead human

body,” based on ME Simms belief that Bailey’s

“anal opening had been cut after his

death.” 11

It is indicative of how sloppy, hasty, and incomplete Thowsen and

LaRochelle’s investigation was that they didn’t

even discover how to correctly spell Blaise’s first name

before arresting her for Bailey’s first-degree murder. In her

statement they spelled her first name Kirsten — not Kirstin.

Six days after Blaise’s arrest, Thowsen returned to Lincoln

County and interviewed Dixie and several other people.

Dixie’s taped statement of Blaise’s conversation

with her differed in important details from Johnson’s claims

of what Dixie said Blaise said to her. Particularly, Dixie said that

Blaise was staying with her parents – not hiding out, and

Dixie did not say her parents were doing anything to hide or get rid of

her car, or camouflage it by painting it. Nor did Blaise ask her not to

tell anyone about the assault she described. Dixie told Justice:Denied

during an interview that Thowsen talked to her for quite some time

before turning on his tape recorder. While the tape recorder was off,

Dixie said Thowsen tried to pressure her to shape her statement to what

he wanted her to say Blaise told her, not what she recollected.

People

in Lincoln County learn

Bailey was killed when Blaise was in Panaca

The Las Vegas Review-Journal

published an article on July 25 that reported Blaise was charged with

murdering Bailey on July 8. That article was the first that the Lobato

family and other people in Panaca knew that July 8 was the date of the

incident Blaise was accused of being involved in.

The Las Vegas Review-Journal

published an article on July 25 that reported Blaise was charged with

murdering Bailey on July 8. That article was the first that the Lobato

family and other people in Panaca knew that July 8 was the date of the

incident Blaise was accused of being involved in.

Blaise’s dad Larry called Thowsen and left a message. When

Thowsen returned the call, Larry told him they had charged the wrong

person because Blaise had been in Panaca all day on the 8th.

Thowsen’s response was “that as far as he was

concerned he had arrested and charged the right person and did not need

any further information.” 12

Crime

lab tests exclude Blaise

Almost a week after Blaise’s arrest, and days after she was

charged, the physical evidence recovered from the crime scene that

included, fingerprints and tire treads, as well as Blaise’s

car and personal effects, were examined by the LVMPD Crime Lab. Blaise

was excluded as the source of four identifiable crime scene

fingerprints. Her metal baseball bat with a porous rubber handle tested

negative for the presence of blood. A spot on the interior of her

car’s driver’s side door panel and on her car seat

cover tested weakly positive after a presumptive luminol test for the

presence of an unknown iron bearing substance (blood contains iron),

but both spots tested negative as being blood when subjected to a

precise confirmatory test.

Somewhat remarkably, the single most important piece of evidence

recovered from the crime scene – Bailey’s severed

penis that was handled by his killer – wasn’t

tested for the presence of identifiable foreign DNA before being buried

with his body.

The crime lab did not analyze the bloody shoeprints leading away from

Bailey’s body, so Blaise’s public defenders

retained a nationally renowned shoeprint expert, William J. Bodziak. He

wrote in his report of March 27, 2002:

“Based on the corresponding dimensions of comparable portions

of other brands of footwear having this generic design, it was

determined the Q1-Q2 impressions most closely correspond to a U.S.

men’s size 9 athletic shoe of this type. …

… Using a standard Brannock foot-measuring device, the

length of the LOBATO right foot equates to U.S. men’s sizes

between 6 to 6-1/2. … The right foot size of KIRSTIN LOBATO

would therefore be at least 2 1/2 sizes smaller than the estimated

crime scene shoe size.” 13

Prosecution’s

lack of

evidence solved by jailhouse informant

On the eve of Blaise’s trial, ten months after her arrest,

the prosecution had no physical, forensic or scientific evidence,

eyewitness or confession linking her to Bailey’s murder.

Neither did they have a single witness who saw her or her car in Las

Vegas on the day of Bailey’s death or for nearly a week

preceding it. In contrast, numerous witnesses said she and her car had

been in Panaca on the 8th and the six days preceding it.

What the prosecution did have was a “jailhouse

informant” – Korinda Martin. Martin claimed that

while they were both in the Clark County Detention Center, Blaise was

loudly “bragging” on several occasions in the open

area of the jail module (where the prisoners watch television and

socialize), “That she was there for murder and that she had

cut a man’s penis off and stuffed it down his

throat.” 14

The accurate details about Bailey’s

murder that Martin claimed Blaise described were included in a July 25,

2001, article about Blaise’s arrest in the Review-Journal,

Las Vegas’ most widely read newspaper that was delivered to

the jail. While Martin’s inaccurate details, such as her

claim that Bailey’s penis was stuffed in his mouth, were not

in the paper.

Blaise’s

trial

Blaise’s trial began on May 8, 2002, in the courtroom of

Clark County District Court Judge Valorie Vega. Blaise’s

attorneys were Clark County Public Defenders Gloria Navarro and Phillip

Kohn. The prosecutors were Assistant D.A.s Sandra DiGiacomo and William

Kephart.

The prosecution tried to influence the jury by generally focusing on a

series of prongs that they represented during closing arguments were

“proven” by the evidence. The

prosecution’s case during Blaise’s trial can be

understood by explaining several of the key prongs they argued. The

following are eight of those prongs, followed by a rebuttal of why each

one didn’t implicate Blaise in Bailey’s murder.

First

prosecution prong

It was too coincidental that a knife would be used to stab at a

man’s groin in two separate incidents in Las Vegas six weeks

apart.

Response

The prosecution ignored that Las Vegas was a crime haven in 2001.

According to the FBI’s 2001 Uniform Crime Report (UCR), Las

Vegas had one of the highest rates of rape in the country, 30% above

the national average, 15

and murder was so commonplace that it was

double the national average, with almost three per week. 16 Also

undermining the prosecution “coincidence” claim is

that in 2001, almost two out of five murders were committed by cutting

or beating – the causes of Bailey’s death. 17

Consequently, it wasn’t unusual for Bailey to be beaten and

stabbed to death, and six weeks earlier for Blaise to have used a knife

to fend off a sexual assault eight miles away in east Las Vegas.

Blaise explained in her statement that she didn’t report the

May 2001 attack because she had reported previous sexual assaults and

the police “basically blew me off. It’s been my

experience that it doesn’t do any good.” 18

Her

non-reporting of the attempted rape is the norm. The U.S. Dept. of

Justice estimates that in 2001 only 39% of rapes and/or sexual assaults

nationwide were reported. 19

Second

prosecution prong

The Budget Suites assault Blaise described and Bailey’s

murder were the same event.

Response

The prosecution’s attempt to transpose the two events ignored

that none of the details in Blaise’s statement and during her

trial testimony matched the crime scene or the circumstances of

Bailey’s death. Not the time, the size of her attacker, the

type of attack, the injuries involved … nothing. There are

at least 24 specific details in her 26-minute statement that are

inconsistent with the facts of Bailey’s murder.

Third

prosecution prong

The prosecution’s “theory of the crime”

was Bailey’s murder resulted from “A drug deal gone

bad.” 20

Response

The prosecution’s “theory of the crime”

was non-fact based speculation for many reasons, including:

- Bailey used crack cocaine, which was in

his system at the time of his death, and witnesses testified he

didn’t use methamphetamines.

- There was no testimony Bailey ever sold

drugs of any kind.

- There was no testimony that Bailey and

Blaise had ever met, or that she knew Bailey was living in the trash

enclosure.

- Multiple witnesses testified that

Blaise used methamphetamines when staying in Las Vegas.

- There was no testimony why Blaise would

drive 170 miles to Las Vegas solely to get meth as the prosecution

alleged, when it was available within walking distance of her

parent’s Panaca house.

Fourth

prosecution prong

Korinda Martin testified that Blaise bragged at the Clark County

Detention Center about killing Bailey.

Response

Undermining Martin’s claims is that the accurate details

about Bailey’s death that Martin testified Blaise said, were

included in a LV Review-Journal article published five days after

Blaise’s arrest. The inaccurate details Martin testified

about weren’t in the media.

Fifth

prosecution prong

The prosecution portrayed Blaise as a bad person of low moral character

who grew up in the sticks of Lincoln County, used methamphetamines, and

on two occasions engaged in amateur exotic dancing in Las Vegas.

Response

Contrary to the prosecution’s intimations, there was no

testimony supporting that because of her upbringing, experiences or

lifestyle Blaise would ever harm anyone except in self-defense.

Sixth

prosecution prong

To explain how Bailey’s extensive injuries could have been

inflicted by a person of Blaise’s slender physique, the

prosecution speculated that after she stabbed him while he was

standing, she repeatedly hit him with the aluminum baseball bat that

she kept in the back seat of her car for self-protection.

Response

That speculation was unsupported by testimony. ME Lary Simms testified

that Bailey “didn’t have any skull fractures that

were depressed like, you know, a bat would depress somebody.”

21

Thomas Wahl, a technician with the LVMPD Crime Lab, testified,

“There was no blood, hairs or tissue recovered from the

aluminum baseball bat or detected on that item.” 22

The bat

has a porous rubber handle that had no trace blood residue.

George Schiro was a forensic scientist of national repute retained by

Blaise’s public defenders to expertly analyze the

prosecution’s physical evidence. He wrote in his Forensic

Science Report:

“There is no documentation of blood spatter above a height of

12 inches on any of the surrounding crime scene surfaces. ...The

confined space of the crime scene enclosures and the lack of [blood]

cast-off indicate that a baseball bat was not used to beat Mr. Bailey.

The beating was more likely due to a pounding or punching type

motion.”

23

Judge Vega, however, did not allow the jury to hear Schiro’s

exculpatory blood ‘spatter’ and ‘cast

off’ testimony. She sustained the prosecution’s

objection that Blaise’s lawyers had not provided them with

proper notice of the scope of his expert testimony.

Seventh

prosecution prong

Since Blaise described stabbing at her assailant as he hovered over

her, the prosecution argued that Bailey was standing with his pants

down when he was stabbed in his groin.

Response

Schiro’s analyzed the evidence for ‘vertically

dripped blood’: “The photographs of his pants also do not indicate the

presence of any vertically dripped blood. This indicates that he did

not receive any bleeding injuries while in a standing

position.” 24

Judge Vega, however, did not allow the jury to hear Schiro’s

exculpatory blood dripping testimony. She sustained the

prosecution’s objection that Blaise’s lawyers had

not provided them with proper notice of the scope of his expert

testimony.

Eighth

prosecution prong

To fit Bailey’s murder with Blaise’s statement that

she was on a methamphetamine binge and awake for the three days

preceding being assaulted, the prosecution speculated she drove her car

from Panaca to Las Vegas on July 6. They further speculated that after

murdering Bailey early on the morning of the 8th, Blaise drove back for

Panaca, arriving around 10 a.m.

Response

The prosecution presented no evidence whatsoever that Blaise was in Las

Vegas on July 6, 7 or 8; numerous people saw Blaise in Panaca on July

6, 7 or 8; and multiple people saw Blaise’s car was parked in

front of her parent’s house from July 2 to July 20.

Furthermore, the prosecution’s argument completely ignored

that Blaise also said she was out of her mind on meth for a week before

and after she was assaulted. Yet, Blaise’s blood sample taken

at the Caliente Clinic on July 5 didn’t test positive for

meth, her urine sample was collected on July 7, and many people saw she

was tired and lethargic for four or five days after arriving in Panaca

on July 2 – not hyped up on meth. Blaise’s

boyfriend Doug Twining has testified that he and Blaise only smoked

marijuana while she was in Las Vegas from July 9 to 13, when her dad

picked her up and took her back to Panaca.

The jury, however, was unaware of some of the alibi testimony

corroborating Blaise’s presence in Panaca from July 2 through

July 9. Citing inadequate notice to the prosecution, Judge Vega barred

the jury from being exposed to that exculpatory information.

Defense

expert Schiro’s

testimony limited

Vega did not allow the jury to hear the majority of defense witness

Schiro’s proposed expert testimony that would have undermined

that the prosecution’s case had any pretense of a scientific

basis.

The jury also did not hear Schiro’s crime scene

reconstruction based on his analysis of the evidence that

Bailey’s murder was a premeditated methodically executed

event.

Schiro was allowed to testify about the testing for the presence of

blood in Blaise’s car. He discussed that both presumptive

luminol and phenolphthalein tests were subject to a high incidence of

false positives, and that negative confirmatory tests indicated to him

that human blood did not cause the weakly positive

presumptive tests for two spots in Blaise’s car.

After he had given his very limited testimony, Schiro, who had spent

the overwhelming majority of his career as a prosecution witness

identifying crime scene evidence that inculpated an accused person,

told reporters in the courthouse hallway what Judge Vega barred him

from telling Blaise’s jurors: “There is no evidence

to tie Ms. Lobato to the crime scene. I feel the evidence is even

exclusionary on her behalf.” 25

The

prosecution’s case

didn’t implicate Blaise in Bailey’s death

At the point that the prosecution and defense rested their cases, none

of the prosecution’s prongs supported implicating Blaise as

Bailey’s killer.

Conclusion

of Blaise’s

trial

The closing arguments were made on Friday, May 18, 2002. DA

DiGiacomo’s argument was based on a multitude of speculations

about how and why Blaise had murdered Bailey.

Blaise’s lawyer Kohn, emphasized that the detectives did not

identify the date of the man’s stabbing they were talking

about when they interrogated Blaise. Furthermore, he pointed out that

the detectives and prosecutors were wrongly assuming she was talking

about Bailey, when none of the details of the incident she described

matched those of his death. Kohn told the jury, “Two people

talking about two different incidents.” 26

He compared the

prosecution of Blaise to the Salem Witch Trials, during which many

innocent women were put to death, “Women who were different,

who were odd and who said stupid things.” 27

DA Kephart asserted in his rebuttal argument that Blaise’s

acknowledgement during her interrogation that she stabbed at a

man’s groin area to fend off his sexual assault constituted a

confession to Bailey’s murder.

Verdict

and sentence

Judge Vega finished reading the jury instructions at 9 p.m. The jury

began deliberations immediately. After five hours they announced they

had arrived at a verdict. At 3 a.m. their verdicts of guilty to both

counts were read in court, and Blaise, who had been free on $50,000

bond, was taken into custody.

Her lawyer Navarro told reporters, “She placed her belief in

the justice system, and she ended up being convicted of a crime that

she did not commit.” 28

On July 2, 2002, Blaise was sentenced to serve a minimum of 40 years

before becoming eligible for parole.

Blaise’s

conviction

reversed by Nevada Supreme Court on September 3, 2004

On September 3, 2004, the Nevada Supreme Court reversed

Blaise’s conviction and remanded her case for a new trial.

Lobato v. State, 96 P.3d 765 (Nev. 09/03/2004) The reversal

was based on Judge Vega’s failure to allow Blaise’s

lawyers to cross-examine Korinda Martin about letters suggesting

leniency that she wanted sent to her sentencing judge. The Court noted,

“The proffered letters and extrinsic evidence relating to

them confirmed Martin’s desperation to obtain an early

release from incarceration and her willingness to adopt a fraudulent

course of action to achieve that goal.” 29

The Court also ruled

that it was prejudicial error for Vega to bar Blaise’ lawyers

from examining the woman the letters were mailed to, as well as

introducing the letters themselves.

New

defense lawyers for Blaise’s retrial

New

defense lawyers for Blaise’s retrial

After reviewing her case and becoming convinced of her innocence, San

Francisco based lawyers Shari Greenberger and Sara Zalkin agreed to

represent Blaise pro-bono during her retrial as co-counsel to her lead

lawyer, David Schieck, with the Clark County Special Public Defenders

Office. In December 2005 Blaise was released pending her retrial on a

$500,000 bond posted by supporters believing in her innocence. For

reasons unknown, Blaise’s attorneys did not move to recuse

Vega from the case in spite of her known bias against Blaise.

Vega’s

pretrial rulings

favor the prosecution

The Nevada Supreme Court was bluntly disappointed with the prejudicial

effect of a number of Judge Vega’s prosecution favorable

rulings during Blaise’s trial. The pretrial motions hearings

for Blaise’s retrial were the first opportunity for Vega, a

former Clark County, Nevada prosecutor, to indicate if she was going to

continue to openly favor her former colleagues. At the conclusion of

those hearings in May 2006, there was no doubt she was not going to be

more balanced. Vega did not grant any defense motion in limine or

suppression outright. The following are some of her rulings.

- The prosecution could

introduce as one of the murder weapons, the bat found in

Blaise’s car when it was searched on July 20, 2001, even

though it had no known connection to Bailey’s murder.

- The prosecution could

introduce pictures and testimony about Blaise’s custom

license plate, even though her car was not found to have any connection

whatsoever with Bailey’s death. Her tire tracks

didn’t match those found at the crime scene and confirmatory

scientific tests excluded the presence of any blood in her car.

- The prosecution could

introduce the “double hearsay” testimony of Laura

Johnson about what she alleged Dixie Tienken said that Blaise had said.

The defense argued, “By seeking to introduce this

impermissible hearsay the State is trying to circumvent the rules of

evidence.” 30

Judge Vega denied the defense’s motion without prejudice as

premature, since Johnson had not yet testified, but the defense could

object for the record when Johnson testified. Thus, Vega cleverly sided

with the prosecution by allowing Johnson to testify about the

“double hearsay” statements without making a ruling

on the motion’s merits.

- The prosecution could

introduce Blaise’s July 20, 2001 statement, even though her

lawyers argued that its details had no relevance to Bailey’s

death, and she advised Thowsen and LaRochelle in the statement that the

incident she described occurred more than a month prior to the

interrogation, and thus more than two weeks prior to Bailey’s

death.

- The prosecution could

introduce presumptive tests of two spots on Blaise’s car that

weakly tested positive (indicating the possible presence of an iron

bearing substance, one of which is blood.), even though the much more

sophisticated and precise confirmatory tests returned negative results

for the presence of blood. Blaise’s lawyers argued in vain

that the jury would be misled that the weakly positive presumptive

tests inferred the presence of blood in Blaise’s car, when

the spots were disproven as blood by the negative confirmatory tests.

- The prosecution could

introduce what amounted to about 140 photographs of the crime scene and

Bailey’s autopsy photos. Blaise’s lawyers argued

unsuccessfully that the cumulative effect of the photos, many that were

near duplicates, would have “the principle effect of inciting

and inflaming the jury, due to graphic depictions of the

victim’s body, the horror of the crime and the cumulative

effect of unnecessarily duplicative photographs.” 31

- Judge Vega also denied the

defense motion to dismiss the charges based on “the

state’s failure to preserve and collect exculpatory

evidence.” Blaise’s lawyers argued the failure to

collect and/or preserve potentially exculpatory crime scene evidence

for testing was a fatal due process violation caused by the

“bad faith,” or at a minimum the “gross

negligence” of the police. Judge Vega ruled that in July 2001

the crime scene investigators and police could not have been expected

to know that fingerprints and scientific testing such as DNA, could

possibly identify Bailey’s murderer(s) from their handling of

any particular item, so they couldn’t have acted in

“bad faith” in failing to collect and preserve the

crime scene evidence.

- Judge Vega also denied a

defense motion to dismiss the charges on the basis that the prosecution

“cannot establish the corpus delicti of the crime with

evidence independent of defendant’s extrajudicial

admissions.” 32

Just weeks before the motion was heard, the Nevada Supreme Court

reiterated, “It has long been black letter law in Nevada that

the corpus delicti of a crime must be proven independently of the

defendant’s extra-judicial admissions.” Edwards v.

State, 132 P.3d 581 (Nev. 04/27/2006). Due to the absence of any

evidence independent of her July 20, 2001, statement and her other

purported extra-judicial statements, Blaise’s lawyers argued

that contrary to the prohibition by the Nevada Supreme Court, the

prosecution relied solely on her extra-judicial statements

“to prove the corpus delicti of Bailey’s

homicide.” 33

Although Vega was aware that there must be independent evidence of

Blaise’s alleged guilt apart from interpretations and

recollections of her purported extra-judicial statements, she

nevertheless denied the motion.

It was evident from Vega’s pre-trial rulings that she was

going to allow the prosecutors free-reign to run a replay of

Blaise’s first trial.

Pubic

hair DNA tests excluded

Blaise in Sept 2006

Several weeks before Blaise’s retrial was scheduled to begin

on September 11, 2006, the prosecution disclosed that it had finally

ordered DNA testing of a pubic hair found during a combing of

Bailey’s pubic hair on the day his body was discovered. The

hair had remained untested for years in his rape kit, even though the

defense had repeatedly asked for it to be tested.

The DNA test excluded Blaise and Bailey as the hair’s source,

but it did reveal that it came from an unidentified male. That finding

was consistent with ME Simms’ testimony during

Blaise’s May 2002 trial that the manner of Bailey’s

murder had homosexual overtones.

Prosecution

Surprise –

No Korinda Martin Testimony During Retrial

The prosecution had let it be known during pretrial proceedings that

they intended to present the same case during Blaise’s

retrial as during her first trial. That, however, wasn’t

true. The defense found out during opening statements that Korinda

Martin wouldn’t be called as a prosecution witness. The

prosecution may have been influenced to omit Martin as a witness

because the defense contended in a pretrial motion to exclude

Martin’s testimony that allowing her testimony would

constitute subornation of perjury by prosecutors DiGiacomo and Kephart.

34 The

prosecutors also knew that based on Vega’s pretrial rulings

they didn’t need Martin’s testimony.

Prosecution

strategy

Since there was no physical, forensic, scientific, circumstantial,

documentary, eyewitness or confession evidence linking Blaise, her car,

or any item of hers within 170 miles of Las Vegas at the time of

Bailey’s murder, the prosecution’s primary strategy

was to argue: ‘It is possible she did it.’ The

defense had timely filed its notice of an alibi defense, and over a

dozen witnesses were scheduled to testify who would place Blaise in

Panaca from July 2 to 9. So the success of the prosecution’s

‘It is possible’ strategy depended on their success

at blocking anyone from testifying about their knowledge of the attack

on Blaise six weeks before Bailey’s murder.

Dixie

Tienken testifies

Dixie had been Blaise’s adult education teacher when she

earned her GED at 17 in 2000. Blaise considered Dixie her friend and

during a three hour conversation in early July 2001 that covered many

topics, Blaise mentioned she had fended off a sexual assault with her

knife when she had been staying in Las Vegas. Dixie didn’t

provide any testimony specifically linking Blaise to Bailey’s

murder, and she actually provided testimony supporting that the attack

Blaise described had occurred between one and two months prior to their

conversation. Although the prosecution treated Dixie as a hostile

witness, her testimony was necessary to lay the foundation for

“Star Witness” Laura Johnson’s

“double hearsay” testimony about what Johnson

claimed Dixie told her Blaise had said.

“Star

Witness” Laura Johnson testifies

During Laura Johnson’s “double hearsay”

testimony, she testified that Dixie said Blaise said that when she was

coming out of a strip club where she worked in Las Vegas, a man

attacked her while his penis was hanging out of his pants and she cut

it off. Johnson also said Dixie said Blaise said she was

“hiding out” at her parents house and her parents

were trying to get rid of her car, or get it painted to hide it. Thus

Johnson provided the magic phrases suggesting Blaise had a

‘guilty mind’, which Dixie denied Blaise told her.

First, that Blaise had been “hiding out” in Panaca,

and second, with the help of her parents she wanted to “get

rid” of her car or “hide” it by painting

it.

ME

Simms

“Games” Bailey’s Time of Death

During Blaise’s Preliminary Hearing in August 2001, ME

Simms’ testified that Bailey died no earlier than 10:36 a.m.

on July 8. That didn’t jibe with Blaise’s statement

that she was attacked during very early morning hours, so at

Blaise’s first trial he “gamed”

Bailey’s time of death by expanding it six hours to the

pre-dawn time of 4:36 a.m. That allowed the prosecution to argue that

the nighttime assault on Blaise and Bailey’s death were the

same event. During Blaise’s retrial Simms further

“gamed” Bailey’s time of death to as

early as 3:50 a.m. 35

Detective

Thowsen testifies

During Detective Thowsen’s direct testimony and

cross-examination, he described informally visiting Diann Parker after

being told she had been at Bailey’s murder scene asking about

him. Thowsen also described her telling him that Bailey beat and raped

her on July 1, after several Mexicans in her apartment complex told him

earlier that day to leave her alone after he slapped and threatened her

while she was drinking beer with them. Thowsen then talked to the

apartment manager who provided him with the names used by the Mexicans.

He said they didn’t cause any trouble. After Thowsen ran a

background check on the names that returned nothing, he

didn’t question the Mexicans.

Although Bailey’s murder was rich with fertile leads, Thowsen

did no more “investigating” into Bailey’s

case until getting a call from Johnson on July 20 about her

conversation with Dixie. He described doing a background check on

Blaise, and contacting the Lincoln County Sheriff that he would be

driving up that afternoon with another detective and a crime scene

analyst to interview a witness and arrest a murder suspect.

During defense attorney David Schieck’s cross-examination,

Thowsen was asked why he didn’t investigate the Budget Suites

attack Blaise described in her statement before arresting her, Thowsen

replied, ‘Because it didn’t happen.’

Thowsen elaborated that every detail in Blaise’s statement

that is inconsistent with Bailey’s crime scene or manner of

death is explainable as “minimizing.” Which he

described as a guilty person’s technique of reducing the

seriousness of what he or she did.

Thowsen’s testimony about Blaise’s alleged

“minimizing” was critical to the prosecution,

because nothing in her statement identified her as involved in

Bailey’s murder. What Schieck didn’t know during

his cross-examination was that Thowsen fabricated his explanation that

she had “minimized” her involvement. According to

the FBI and other experts in police interrogation techniques,

“minimizing” is what a detective does to induce a

suspect who has already admitted to an identifiable level of

involvement in a crime to further incriminate him or herself by

confessing to more specific details. The following are excerpts from an

article in the August 2005 issue of the FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin,

titled, “Reducing a Guilty Suspect’s Resistance to

Confessing”:

The investigator presents the acceptable reasons to confess, usually in

one of three … categories: rationalizations, projections of

blame, and minimizations. … investigators can try to reduce,

or minimize, the heinous nature of the crime so it produces less guilt

or shame for the suspect.. …

…

Because the focus of the rational choice theory is centered on

self-interest, projecting the blame on anything else is appropriate to

reduce the suspect’s feelings of guilt. … the

investigator can minimize the woman’s shame by acknowledging

her righteousness …

…

To make the crime more acceptable, the investigator can minimize the

suspect’s deviant actions by explaining how he has seemingly

overcome overwhelming natural circumstances…

…

Regarding minimizations, the investigators could suggest that engaging

in property crimes to obtain the American dream offers a much more

acceptable route than committing violent crimes.

…

To minimize the crime, the investigator can convince the suspect that

his actions were minor offenses … 36

The preceding explanation of “minimization” in an

official FBI publication clarifies that during Blaise’s

interrogation neither Thowsen nor LaRochelle

“minimized” her involvement in the assault she

described. Further undermining Thowsen’s credibility about

“minimization” is that Blaise said nothing to

reduce her involvement in the assault she described in her statement.

Thowsen’s false testimony about

“minimizing” to explain away the absence of

similarity between Blaise’s statement and the details of

Bailey’s death wasn’t a minor infraction. It was

the cornerstone of his testimony.

Prosecution’s

case

lacked evidence implicating Blaise

There were several dozen witnesses during the prosecution’s

nearly three-week case. Those witnesses included police officers,

several crime lab technicians, medical examiner’s office

personnel, relatives of Bailey, and friends and acquaintances of

Blaise. What is notable about those witnesses is that not a single one

provided any testimony linking Blaise to any involvement in

Bailey’s murder, or that on July 8 she had been within 170

miles of Las Vegas, or that she had ever met Bailey. Not even the two

key witnesses, Johnson and Thowsen, provided any testimony that was

anything more than conjecture that Blaise possibly could have been

referring to Bailey’s death when she described fending off a

sexual assault with her knife.

That lack of testimonial evidence was backed up by the absence of any

physical, forensic or scientific evidence that Blaise or her car was

present at the crime scene. Her involvement was in fact undermined by

the crime scene fingerprints that excluded her, the DNA test of the

pubic hair found on Bailey’s body that excluded her, the

bloody male shoeprints that excluded her, the tire tracks that excluded

her car, and the DNA on chewing gum found on the cardboard covering

Bailey’s body that excluded her.

During cross-examination of law enforcement witnesses, the defense was

repeatedly able to expose the multiple deficiencies in the collection,

preservation, and/or testing of crime scene evidence. The portrait

painted by the defense’s cross-examination was that with a

few exceptions, the LV Metro PD handled Bailey’s crime scene

and investigation like they were a cross between the Keystone Cops and

rank amateurs.

Two

defense experts

The defense did not retain Schiro for Blaise’s retrial, but

it did enlist two experts who testified, Dr. Michael Laufer and Brent

Turvey.

Dr.

Michael Laufer testifies

Bailey was likely murdered with scissors

Dr. Michael Laufer is associated with Stanford Medical School and the

nationally recognized inventor of more than 100 medically related

products.

In the course of reviewing the autopsy report, and autopsy and crime

scene photos, Laufer began doubting that Bailey’s stab and

slashing wounds were caused by a knife, as he had been told when he

agreed to review the case. He noticed they resembled scissors wounds he

had treated during his years as an emergency room doctor. So he

proceeded to conduct a photographed controlled experiment to see if he

could duplicate Bailey’s wounds by stabbing scissors into a

flesh substitute – foam rubber tightly covered with ultra

suede.

In his final report, dated September 24, 2006, Laufer determined that

Bailey’s stab wounds were consistent with being caused by

scissors, and that barber scissors with a finger hook were the most

likely type used to inflict Bailey’s wounds. He also

concluded that scissors were likely used to snip his carotid artery,

and “The penile amputation was most likely performed with

scissors.” 37

Laufer’s experiment

that duplicated a wound to Bailey’s abdomen disclosed

“a “ring distance” between the inside of

the second finger and the inside of the fifth finger of the

assailant’s hand of at least 5.8 cm.” 38

The “ring

distance” of Blaise’s hand was measured to be 4.3

cm. Thus Laufer concluded her hand is much smaller than

Bailey’s assailant.

Laufer’s experiment

that duplicated a wound to Bailey’s abdomen disclosed

“a “ring distance” between the inside of

the second finger and the inside of the fifth finger of the

assailant’s hand of at least 5.8 cm.” 38

The “ring

distance” of Blaise’s hand was measured to be 4.3

cm. Thus Laufer concluded her hand is much smaller than

Bailey’s assailant.

Laufer also determined that because the bleeding of Bailey’s

blood stopped at the waist level of his pants, the wounds above his

waist were inflicted while his pants were pulled up.

Laufer testified to his findings about Bailey’s wounds and

cause of death on direct examination. The prosecution, however,

successfully blocked his testimony about the case’s extensive

blood evidence. Judge Vega agreed with the prosecutors that the defense

had not provided the required notice about the extent of

Laufer’s expert testimony.

Kephart was taken aback during his cross-examination, when Laufer

testified that he provided his expertise in Blaise’s case pro

bono. Laufer said, “The first thing I was told [by defense

lawyer Greenberger] was, “We don’t have any

money.””

Brent

Turvey testifies no

physical evidence implicates Blaise in Bailey’s murder

The other defense expert was Brent Turvey, a forensic scientist and

criminal profiler. After analyzing a large number of case reports and

documents, Turvey completed a report dated October 17, 2005. His

findings were:

1. There is no physical evidence associating Kirstin

“Blaise” Lobato, or her vehicle (a red 1984 Fiero),

to the crime scene.

2. The offender in this case would have transferred bloodstains to

specific areas of any vehicle they entered and operated.

3. The failure of Luminol to luminesce at any of the requisite sites in

the defendant’s vehicle is a reasonably certain indication

that blood was not ever present, despite any conventional attempts at

cleaning.

4.There are several items of potentially exculpatory evidence that were

present on or with the body at the crime scene but subsequently not

submitted to the crime lab for analysis.

5. A primary motive in this case is directed anger expressed in the

form of brutal injury, overkill and sexual punishment to the

victim’s genitals.

6. The wound patterns in this case may be used to support a theory of

multiple assailants. 39

Turvey testified to his findings on direct examination. Key points of

his testimony revolved around forensic science’s

“exchange principle,” which is that

“every contact leaves a trace” and, “no

evidence means no proof of contact.” 40

The “exchange principle” is the basis of his

conclusion that there is no physical evidence Blaise was involved in

Bailey’s murder.

Turvey’s cross-examination was much more contentious than

Laufer’s. The biggest fireworks occurred when Turvey resisted

DiGiacomo’s attempts to pressure him to acknowledge that the

two spots in Blaise’s car that weakly tested positive after a

presumptive test, “possibly” could be blood. Turvey

repeatedly responded that the much more precise confirmatory testing of

the spots were negative for blood, so the idea it was blood

“had to be let go.”

Four

witnesses not allowed to

testify attack on Blaise was before Bailey’s death

The prosecution knew that prior to Bailey’s murder Blaise

talked with at least five people about the May 2001 Budget Suites

assault. Those five people are Steve Pyszkowski, Kathy Renninger,

Michelle Austria, Heather McBride, and Blaise’s dad, Larry

Lobato.

During Blaise’s first trial Vega had allowed Pyszkowski,

Austria and McBride to testify that they were told about the assault

against Blaise in Las Vegas on days that ranged from a month to six

days preceding Bailey’s murder on July 8. Larry was told by

Blaise about the attack in late June 2001, but he wasn’t

called as a witness by the defense.

Four of those people, Pyszkowski, Austria, McBride, and Larry testified

at Blaise’s retrial, but Judge Vega blocked all of them from

testifying about their knowledge of the May assault, by sustaining the

prosecution’s objections it was hearsay.

Alibi

witnesses

Thirteen people testified that they saw Blaise in Panaca between July 2

and July 9. 41

Ten of those people testified they saw her on the weekend of July 7 and

8. All of the relatives, acquaintances, and neighbors who also

testified about seeing Blaise’s car parked in front of her

parents house said they never saw it moved or parked in a different

position on the city street behind a utility trailer, after she arrived

from Las Vegas on July 2, until the police took it away on July 20.

Kristina

Paulette

During LVMPD Crime Lab technician Kristina Paulette’s

testimony on September 25 as a prosecution witness, she described the

DNA test results of a pubic hair combed from Bailey’s public

hair that remained untested in Bailey’s rape kit for more

than five years. The test not only excluded Blaise, but it was from an

unidentified male. After the retrial began DiGiacomo instructed the

police crime lab to perform DNA testing of three cigarette butts found

on Bailey’s body. That DNA report was issued two days after

Paulette testified for the prosecution, so she was called as a defense

witness on October 2. She testified that one butt did not have

isolatable DNA, another had Bailey’s DNA (from his blood) and

the DNA of an unidentifiable person, and the third only had the DNA of

an unidentified male. Paulette testified that Blaise was conclusively

excluded as a source of the DNA on the second and third cigarette butts.

Closing

arguments

The personality differences between the two prosecutors and

Blaise’s lawyer conducting the closing, David Schieck were

stark. Prosecutor DiGiacomo has the bearing and mannerisms of a

spoiled, petulant child. Prosecutor Kephart has a forceful personality

and the mannerisms of a snake-oil salesman. While Schieck has an

earnest, low key manner.

DiGiacomo’s

closing

argument

DiGiacomo’s closing revolved around the theme: It is possible

Blaise killed Bailey.

To support her ‘It’s possible she did it’

claim, DiGiacomo speculated about numerous allegations that were

unsupported by any trial evidence. She even had a PowerPoint

presentation laying out her supposition that Blaise was

Bailey’s killer. Although DiGiacomo made her arguments

without caution or restraint, Blaise’s lawyers

didn’t object.

Schieck’s

closing

argument

Schieck’s closing was built on several interrelated themes:

the crime scene evidence that was collected and tested excludes Blaise;

there is nothing in her statement that incriminates her in

Bailey’s murder; nothing in her possession or her car links

her to Bailey’s murder; the unrebutted alibi testimony of

nearly a dozen people establishes she was in Panaca the entire day of

July 8; and because of the complete absence of inculpatory evidence,

the prosecution was seeking to have Blaise convicted on their

speculation it was possible she killed Bailey – and not proof

beyond a reasonable doubt.

He described the prosecution’s case as:

“It’s possible it happened this way;”

“somehow Blaise came into contact with Mr. Bailey;”

“Somehow, somehow, somehow, it goes on and on.”

Schieck explained that the prosecution was supporting their scenario of

the crime with the argument, “There is nothing to disprove

this so it must be true.” He told the jurors, “The

prosecution is actually defending themselves from the lack of evidence

and trying to convince you that somehow they have proved anything in

this case.”

Schieck plainly asked the jury, “Isn’t it possible

that she wasn’t there and that’s why they have no

evidence? Isn’t it possible they are prosecuting an innocent

person? Isn’t that a possibility if they want to talk about

possibilities?”

Schieck emphasized, “What happened in this case is a snap

judgment was made to arrest Blaise Lobato in Panaca, Nevada, and for

the next five years the state and the detectives have attempted to

prove their case after they made their arrest instead of doing it the

right way of getting your facts straight before you arrest someone and

charge them with murder.”

He encouraged the jurors to listen to Blaise’s taped

statement, telling them, “There is no evidence in that

statement that is going to convict her in this case.”

He also told the jury that when the defense presents an alibi defense,

the burden is on the state to disprove the alibi beyond a reasonable

doubt. Yet the prosecution presented no testimonial or documentary

evidence rebutting Blaise’s alibi of continuously being in

Panaca from the afternoon of July 2 until the early morning of July 9.

So she wasn’t even in Las Vegas when Bailey was murdered on

the 8th.

Schieck gave the jury a bit of a history lesson by telling them that

the prosecution’s burden of proving a defendant guilty beyond

a reasonable doubt was embedded in the Bill of Rights to prevent a

person such as Blaise from being convicted without any evidence. He

explained, “The burden of proof is beyond a reasonable doubt,

not, it’s possible.”

Kephart’s

rebuttal

closing argument

Kephart is an experienced prosecutor who knows from more than 100 jury

trials that evidence of a defendant’s guilt isn’t

necessary to win a conviction, as long as he is able to push the jurors

emotional buttons that make them bypass the thought process and feel a

defendant is guilty without being able to coherently articulate why.

Since the prosecution had no direct or circumstantial evidence upon

which to base an argument for the jury to find Blaise guilty, Kephart

resorted during his rebuttal to using his forceful personality to

command the jury’s attention while he made an emotion laden

zealous argument for a guilty verdict based on the theme that it was

too coincidental for a man to be non-fatally wounded by having his

groin area stabbed or cut as Blaise described in her statement, and six

weeks later for another man across town to have his penis severed after

he was dead.

Kephart’s argument bet that the all-white middle-class jury

could be induced to disregard that no evidence tied Blaise to

Bailey’s murder if they could be convinced that in July 2001

she was a thoroughly bad and depraved young women who would do anything

to satisfy what he alleged was her meth craving. Kephart’s

wild-eyed ranting about Blaise during his closing was in some ways

reminiscent of old film clips of fevered denunciations by Hitler and

other Nazis of Jews as subhuman and deserving of punishment.

Kephart’s closing emotional appeal to the jury was showing

them a large blow-up of Blaise’s picture taken when she was

arrested in Panaca on July 20. He thundered that the short-haired

bleach blond 18-year-old with no make-up shown in the picture is who

the jury was judging and should convict – not the attractive

23-year-old brunette with long “swept-back” hair

sitting at the defense table. As with DiGiacomo’s closing,

the defense allowed Kephart to run-off his mouth unrestrained by

objections.

Jury’s

verdict

After Kephart’s fire-breathing evangelical closing, some

trial observers might have been concerned the jury would rush out like

a lynch mob and convict Blaise in short order while in a fevered state

of mind. The jury began deliberating at 6:45 p.m. on Thursday, October

5, and when they requested to go home at midnight, it was known that at

least one juror wanted to at least consider the evidence. The jury

resumed deliberating at 8:30 a.m. on Friday, the day before the

beginning of the Columbus Day holiday weekend. In mid-afternoon, after

more than ten hours of deliberation, they notified the bailiff they had

reached a verdict.

The jury convicted Blaise of voluntary manslaughter with a deadly

weapon and sexual penetration of a dead body. Schieck moved for

continuation of Blaise’s release on $500,000 bond. Kephart

opposed it, arguing she was a flight risk because she hadn’t

personally put up the bond money. Vega adopted Kephart’s

position and Blaise was taken into custody.

After the verdict, both Kephart and Schieck publicly expressed the

opinion that it was a compromise: some jurors wanted to acquit Blaise,

and others wanted to convict her of first or second-degree murder. But

on the eve of a holiday weekend, the jurors settled in the middle

rather than continue deliberating through the holiday, and possibly

even then be unable to reach a unanimous non-compromise verdict.

Judge Vega went along with the recommendation of her former colleagues

in the Clark County DA’s office and sentenced Blaise to the

maximum of 13 to 45 years in prison on February 2, 2007, even though

she was eligible for probation, she received a positive psychological

evaluation from both a prosecution and a defense expert, and there was

no evidence presented during the sentencing hearing that she poses any

danger to the community.

Conclusion

Almost six years after Duran Bailey’s murder, all the

physical evidence and evaluation of the crime scene points exclusively

to one or more males as the perpetrator. Yet Blaise has twice been

convicted in this death without any evidence whatsoever she was within

170 miles of Las Vegas at the time of his murder.

An examination of Blaise’s case reveals deep flaws in the

collection and testing of evidence, and the investigation, prosecution

and adjudication of serious crimes in Clark County, Nevada, and in a

larger sense, jurisdictions all across the United States. That is

because the same bureaucratic police, prosecution and judicial

processes and influences involved in Blaise’s case are

typical of those that prevail throughout the country. It is sobering to

consider, but there is every reason to think Blaise could have been

convicted – twice – anywhere else under the same

circumstances of an underfunded defense, detectives unconcerned about

the truth, prosecutors obsessed with “winning at all

costs,” and an overtly prosecution friendly judge who is a

former assistant DA. 42

Kirstin can

be written at:

Kirstin

Lobato 95558

FMWCC

4370

Smiley Road

Las

Vegas, NV 89115-1808

Kirstin’s

outside contact is:

Michelle

Ravell

Email: Justice4kirstin@cox.net

The

Free Kirstin’s Website, http://www.justice4Kirstin.com

Contact

Hans Sherrer at: hsherrer@justicedenied.org

Endnotes:

1 Autopsy Report: Pathologic

Examination On The Body Of Duran Bailey, Clark County Coroner, July 9,

2001 (Las Vegas, NV).

2 Simms expressed that opinion

during Kirstin “Blaise” Lobato’s

Preliminary Hearing on August 7, 2001, based on the fact that when

examined by the coroner’s investigator at the crime scene,

“The body wasn’t manifesting any significant degree

of decomposition, so I would say he had died a lot closer to the time

he was discovered than not.” See, State v. Lobato, Case No.

C177394, Reporter’s Transcript of Preliminary Hearing, August

7, 2001, 32-33.

3 The State of Nevada v. Kirstin

Blaise Lobato, No. 40370, Transcript Vol. 5, 45, Testimony of Diann

Parker, May 14, 2002.

4 Id., 46

5 Statement to Las Vegas

Metropolitan Police Department by Laura Linn Johnson, Event

#010708-2410, July 20, 2001, pp. 2-3.

6 Contrary to Johnson’s

assertion, Lincoln County District Attorney Greg Barlow reports that

Blaise has never been investigated, arrested, convicted, sentenced, or

served any probationary term for any alleged violation of any law in

Lincoln County. District Attorney Barlow provided that information in a

letter dated January 4, 2007, to The Justice Institute/Justice:Denied,

in response to a Public Records Law request.

7 This relating of events is a

composite of Blaise’s statement to Detectives Thowsen and

LaRochelle on July 20, 2001, and conversations she had with other

people. See, Statement to Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department by

Kirsten Blaise Lobato, Event #010708-2410, July 20, 2001, (hereinafter,

“Blaise’s Statement”).

8 The testimony of Doug Twining

establishes the assault occurred on May 23, 24 or 25, just before the

2001 Memorial Day weekend.

9 These 24 details are documented in

two charts at,

http://justicedenied.org/issue/issue_34/statement_differences.htm

10 The State of Nevada v. Kirstin

Blaise Lobato, No. 01F12209X, Dept. 2, Criminal Complaint, July 23,

2001.

11 The State of Nevada v. Kirstin

Blaise Lobato, No. 01F12209X, Dept. 2, Amended Criminal Complaint, July

26, 2001.

12 Larry Lobato testimony on

October 3, 2006, at retrial of Kirstin Blaise Lobato.

13 William J Bodziak, Footwear

Examination Report, Forensic Consultant Services, March 27, 2002.

14 The State of Nevada v. Kirstin

Blaise Lobato, No. 40370, Transcript Vol. 3, 169, Testimony of Korinda

Martin, May 10, 2002.

15 Crime in the United States 2001,

Uniform Crime Reports, FBI, U.S. DOJ, Washington D.C., Table 6, Index

of Crime (There were 447 reported rapes in Las Vegas in 2001.).

16 Id. (There were 133 identifiable

murders in Las Vegas in 2001).

17 Crime in the United States 2001,

Uniform Crime Reports, Federal Bureau of Investigation, U.S. Department

of Justice, Washington D.C., Table 2.9, Murder, Types of Weapons Used.

(A sharp object (knife, scissors, etc.) was involved in 13% of all

murders, and 24% of murders were committed with fists or an unknown

weapon.)

18 ‘Sensitive’

Defendant Denies Mutilation Slaying Charge, Glenn Puit, Las Vegas

Review-Journal, May 16, 2002.

19 “Reporting to the

police,” 2001 National Crime Victimization Survey, Bureau of

Justice Statistics (U. S. Department of Justice), p. 10. At,

http://www.ojp.gov/bjs/pub/pdf/cv01.pdf.

20 Kephart didn’t just

argue this in court, but explained it to journalists during the jurors

deliberations and then after Blaise was sentenced on August 28, 2002.

See, Homeless man's killer sentenced, Las Vegas Review-Journal, August

28, 2002; Jurors Deliberate Severed Penis Slaying, Glen Puit, Las Vegas

Review-Journal, May 17, 2002.

21 The State of Nevada v. Kirstin

Blaise Lobato, No. 40370, Transcript Vol. 2, 38, Testimony of Lary

Simms, May 9, 2002.

22 The State of Nevada v. Kirstin

Lobato, No. 40370, Transcript Vol. 4, 124, Testimony of Thomas Wahl,

May 13, 2002.

23 Crime Scene Reconstruction and

Forensic Science Interpretation in State v. Lobato, Case No. C177394.

Forensic Science Resources, Case No. FSR2-02, May 31, 2002, p. 3. (Bold

in original.) This report was completed after Blaise’s trial.

24 Id., p. 3. (Bold in

original.)

25 Expert’s Testimony

Limited, Las Vegas Review-Journal, May 17, 2002. (emphasis added)

26 Jurors Deliberate Severed Penis

Slaying, Glenn Puit (staff), Las Vegas Review-Journal, May 17, 2002.

27 Id.

28 Convicted Killer Turned Down

Plea Deal, Las Vegas Journal-Review, May 29, 2002.

29 Lobato v. State, 96 P.3d 765

(Nev. 09/03/2004)

30 Defendant Lobato’s

Notice Of Motion And Motion In Limine To Exclude Testimony Of Laura

Johnson, State v. Lobato, No C177394, District Court, Clark County, NV,

p. 12.

31 Defendant Lobato’s

Notice Of Motion And Motion In Limine To Exclude Inflammatory and

Cumulative Photographs, State v. Lobato, Case No. C177394, Dept II,

District Court, Clark County, Nevada, p. 4.

32 Kirstin Lobato’s

Motion To Dismiss Because The State Cannot Establish The Corpus Delicti

Of The Crime With Evidence Independent Of Defendant’s

Extrajudicial Admissions, State v. Lobato, Case No. C177394, Dept II,

District Court, Clark County, Nevada.

33 Id. at 6.

34 Defendant Lobato’s

Notice Of Motion And Motion In Limine To Exclude Witness Korinda

Martin’s Testimony …, State v. Lobato, Case No.

C177394 (“…the presentation of said testimony is

tantamount to suborning perjury.”)

35 Simms has twice revised his

estimate of Bailey’s time of death, even though the

information upon which he based his initial estimate remains unchanged.

36 Reducing a Guilty

Suspect’s Resistance to Confessing: Applying Criminological

Theory to Interrogation Theme Development, By Brian Parsi Boetig, M.S.,

FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin, August 2005 Volume 74 Number 8, United

States Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation

Washington, DC 20535-0001. (Emphasis added to original.)

37 Report Re: Lobato, Michael D.

Laufer, MD , September 24, 2006, Interpretation of findings, No. 8., p.

3.

38 Id., Conclusions, No. 5., p. 4.

39 Forensic Examination Report,

Brent E. Turvey, MS, October 17, 2005, p. 2.

40 Brent Turvey’s

testimony on October 2, 2006, at Kirstin “Blaise”

Lobato’s retrial.

41 A chart of the alibi witnesses

is at, http://www.justicedenied.org/issue/issue_34/ alibi.htm

42 For a discussion of the

dominance of bureaucratic processes in the United States, see, The

Inhumanity of Government Bureaucracies, Hans Sherrer, The Independent

Review, Vol. 5, No. 2, Fall 2000, 249-264.

New

defense lawyers for Blaise’s retrial

New

defense lawyers for Blaise’s retrial

The Las Vegas Review-Journal

published an article on July 25 that reported Blaise was charged with

murdering Bailey on July 8. That article was the first that the Lobato

family and other people in Panaca knew that July 8 was the date of the

incident Blaise was accused of being involved in.

The Las Vegas Review-Journal

published an article on July 25 that reported Blaise was charged with

murdering Bailey on July 8. That article was the first that the Lobato

family and other people in Panaca knew that July 8 was the date of the

incident Blaise was accused of being involved in. New

defense lawyers for Blaise’s retrial

New

defense lawyers for Blaise’s retrial Laufer’s experiment

that duplicated a wound to Bailey’s abdomen disclosed

“a “ring distance” between the inside of

the second finger and the inside of the fifth finger of the

assailant’s hand of at least 5.8 cm.” 38

The “ring

distance” of Blaise’s hand was measured to be 4.3

cm. Thus Laufer concluded her hand is much smaller than

Bailey’s assailant.

Laufer’s experiment

that duplicated a wound to Bailey’s abdomen disclosed

“a “ring distance” between the inside of

the second finger and the inside of the fifth finger of the

assailant’s hand of at least 5.8 cm.” 38

The “ring

distance” of Blaise’s hand was measured to be 4.3

cm. Thus Laufer concluded her hand is much smaller than

Bailey’s assailant.