A Mistaken Identification Leads to a Wrongful Conviction and Death Sentence

The Tony Ford Story

On December 18, 1991, two people broke in to the home of Myra Concepcion Murillo in El Paso, Texas. Saying they needed to see “the man of the house,” and demanding to know where “the money” was, the two men became angry when their demands were met with confusion. Within moments, one of the men shot and killed Ms. Murillo’s eighteen-year-old son, Armando, then shot Ms. Murillo and her two daughters. Ms. Murillo and her daughters survived.

The prosecution’s case at trial turned on the daughters’ identification of Tony Ford from a photo array as one of the two men who broke in to their home and as the one who did the shooting. In his defense, Tony testified that he was not involved in the home break-in though he had driven the two men to the Murillo’s house. He testified that he was outside in the vehicle waiting for the two men when the break-in occurred and that he did not know that the men planned to break in to the house and kill people.

A man named Van Belton (Van) was charged along with Tony Ford with breaking in to the Murillo’s home. Van was the only person initially identified by Ms. Murillo’s daughters. One of them recognized him from high school. Both daughters said Van was the second man involved in the break-in and was not the shooter. Neither knew the other man. After Van was arrested, he told the police that Tony was the other person. In Tony’s statement to the police and in his testimony at trial, he confirmed that Van was one of the two men who broke in to the Murillo’s home, but he testified that the second man was Van’s brother Victor Belton (Victor).

Tony Ford’s Lawyers Tried To Question The Reliability Of His Identification

At trial, the critical factual question for the jury to resolve was whether the Murillo’s subsequent identification of Tony Ford from a photo array was reliable.

Based on all the other evidence, the Murillo sisters’ identification of Tony appeared to be a mistake, because no other evidence connected him directly to the crime:

In a search of Tony’s home after the crime, nothing at all relating to the crime was found.

By contrast, property taken from the Murillo’s house was located at Van and Victor Belton’s home.

The only physical evidence suggesting a link to Tony was inconclusive. Three wool fibers found on Armando Murillo’s shirt were determined to be similar in color, size, and appearance to the wool fibers from Tony’s trench coat. The state’s expert testified that the fibers “could” have come from the coat. In her lab report, this witness was even more equivocal. She reported that “[t]he three dark gray wool fibers were similar in color to some wool fibers in the overcoat and could have originated in the coat or any wool garment of a gray/purple color.”

This coat also had a small stain on the inside of a pocket too small to type or test. The prosecution’s forensic examiner identified this stain as blood, but acknowledged that it was “consistent” with someone cutting a finger and putting his hand in the coat. Even this testimony was overstated. In the lab report, the witness expressed doubt about whether this stain was even blood: “The coat was treated with luminol reagent, resulting in a positive presumptive reaction for blood. Subsequent analysis using Takiyama, a confirmation test for blood, indicated no detectable blood present.” Thus, this witness’s testimony failed to link Tony’s coat to the crime at all.

Finally, even if the jury saw the physical evidence as connecting Tony’s coat to the crime, there was an explanation for that that was consistent with Tony’s account of what happened: Tony loaned the coat to Victor shortly before the crime, so that Victor could conceal his gun under the coat.

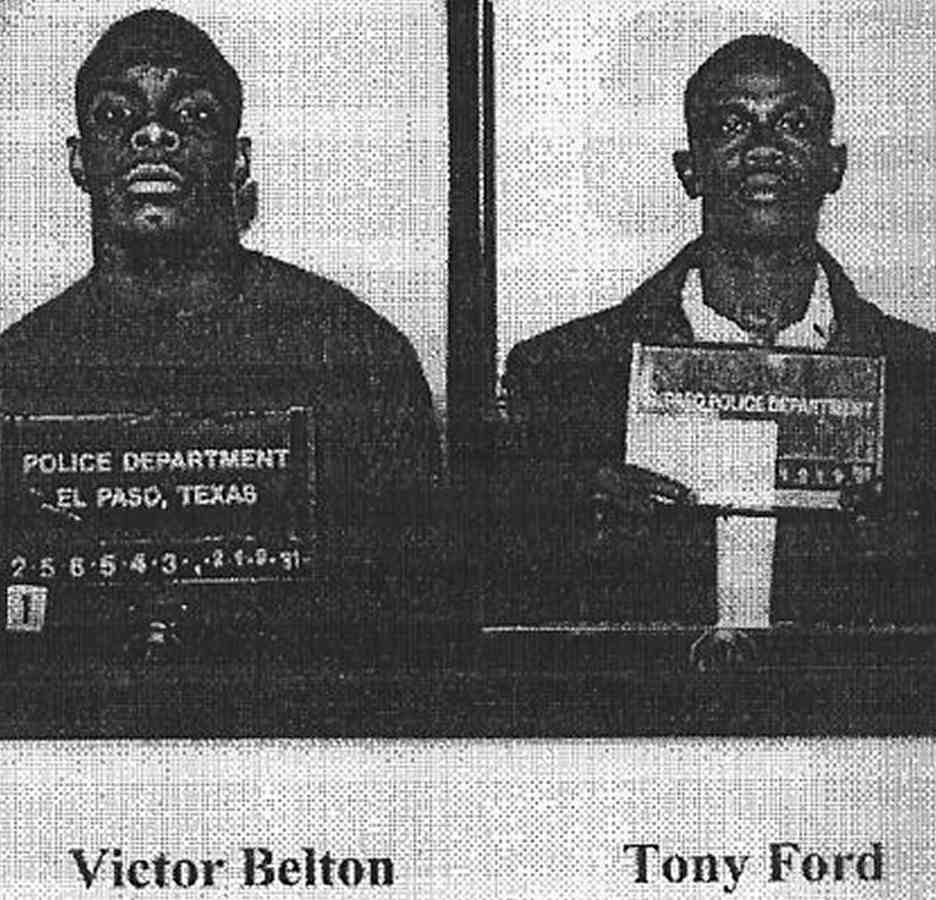

To show how the Murillo’s could have mistakenly identified Tony, defense counsel introduced the booking photograph of Victor from December 19, 1991. Victor had been arrested at his parents’ house, along with his brother Van, in the early morning hours of December 19, 1991. Van was charged with the crimes that occurred at the Murillo’s house, and Victor, with assaulting the officers who were attempting to arrest Van and who had arrested their father for hindering the arrest of Van. The defense also introduced the booking sheets for Tony and for Victor. The sheets showed that as of December 19, 1991, both young men were 5'-8" tall. Victor weighed 156 pounds, while Tony weighed 150 pounds. Tony was 18 years, 6 months old; Victor was 17 years, 8 months old – only 10 months younger than Tony. As the photographs of Victor and Tony show, they also looked very similar. An eyewitness or victim could have mistakenly identified Victor Belton as Tony Ford.

Mugshots of Victor Belton and Tony Ford

Tony’s lawyers also tried to present additional evidence about the unreliability and inaccuracy of the Murillo sisters’ identifications. Before trial, they asked the court for funds to hire Dr. Roy Malpass, a highly regarded El Paso expert in eyewitness identification. The trial judge denied their request. Relying on the daughter’s questionable identification of Tony, the jury convicted him on July 9, 1993. He was subsequently sentenced to death.

After exhausting his state court appeals, Tony filed a federal habeas corpus petition. In response to Tony’s request, the court provided the funds for Tony’s lawyers to consult with Malpass so that they could show what Tony’s trial attorneys could have presented to the jury had their request for Malpass’s assistance at trial been granted.

Working with Tony’s federal court lawyers, Malpass conducted two empirical studies, based on well-established scientific principles, to determine whether the process by which the Murillo sisters identified Tony – by looking at an array of six photographs of different people, one of whom was Tony – was likely to produce a mistaken identification.

The first study compared the similarity of facial features and appearance of Tony, the other five people included in the photo array, and Victor. The results showed that Tony and Victor were, by far, the most similar looking. Thus, someone who had seen Victor actually commit the crime and who was shown the photo array with Tony’s picture in it would have been drawn to Tony’s picture.

This is exactly what happened in the second study Malpass conducted. The second study was designed to determine whether the photo array from which the Murillo sisters picked out Tony was “suggestive” – that is, was composed of photographs of people different enough in appearance from Tony that he stood out and was more likely be picked out by persons given a verbal description of Tony’s facial features. Based on this study, Malpass concluded that the photo array was substantially biased to lead to the identification of Mr. Ford’s photograph: His photo was four times more likely to be picked out by research participants. A fair and non-suggestive photo array would have lead research participants to pick out each photo with approximately the same frequency.

The importance of this, as established by the first study, is that Victor looked remarkably like Tony. Thus, if the person the Murillo sisters saw shoot their brother was Victor they would have been highly likely to pick Tony out of the photo array they were shown – even though they had never seen him before.

Had the trial court provided the funding for Malpass’s assistance, he also could have provided additional critical information to the jury in their effort to determine whether the Murillo sisters’ identifications were reliable:

Because the Murillo’s were Latino

and the suspects were black, Malpass would have explained that the risk

of a mistaken identification was higher. In a study based in El Paso,

involving the cross-racial identification of a black suspect by Latino

eyewitnesses, the results revealed that 67% of the time,

when the Latino witness identified a black suspect, the witness was

mistaken. By contrast, when Latino witnesses identified Latino

suspects, they were mistaken only 29% of the time.

Numerous other studies of this phenomenon have confirmed this

extraordinarily high likelihood of mistake in cross-racial

identifications.

Malpass would also have explained that the presence

of a weapon that is used in a threatening manner, as it was in the

Murillo’s home, reduces the probability that an

identification is accurate.

Malpass would have explained that the Murillo

sisters’ unwavering certainty that their identifications were

accurate (each testifying, “I will never forget his

face”) did not mean that they were accurate. Research has

established that eyewitness certainty is not correlated with the

accuracy of the identification. Among subjects who are highly certain

of their identifications, the error rate of 50% is very high. This was

especially important information for the jury to have had, because in

post-trial interviews, members of Tony’s jury revealed that

one of the jurors had once been the victim of a crime and this juror

told the other jurors that she, like the Murillo sisters, would never

forget what the assailant looked like.

Finally, Malpass would have addressed another factor that increased the likelihood that the identification of Tony was unreliable. The exposure of an eyewitness to a photograph of the suspect before he or she views the suspect’s photograph as part of a photo spread increases the likelihood that the eyewitness will identify the same suspect in the photo spread even if the identification is erroneous. Before she viewed the photo spread, one of the Murillo sisters saw Tony’s photograph in a local newspaper story that identified him as a suspect in her family’s case.

There was some question about whether the first one of the Murillo sisters (Myra) to identify Tony’s photograph had – in fact – picked his photograph out of the photo spread. Ms. Murillo and Detective Lowe both testified at a pretrial hearing that Ms. Murillo picked Tony’s photograph out of the photo spread at 4:10 pm on December 19, 1991. In addition, both Ms. Murillo and Detective Lowe testified that Ms. Murillo signed the back of Tony’s photograph and noted the date and time as December 19, 1991 and 4:10 pm. Tony’s photograph appeared in the number 5 position in the photo spread. Two minutes after Ms. Murillo allegedly signed the back of Tony’s photograph, at 4:12 pm, Detective Lowe typed a statement for Ms. Murillo to sign concerning the number of the photo she picked out of the photo spread. In that statement Detective Lowe typed, “I have recognized the man whose picture is numbered 4 as the man who shot and killed my brother.” When Ms. Murillo signed the statement thereafter, the reference to photograph number 4 is overwritten and the numeral “5” is written in by hand. There are no initials by this overwriting, and there is no note explaining what happened. There is just a change in the number, from the photo of someone else to the photo of Tony.

Obviously, this discrepancy raised questions about the integrity of the process by which Tony was initially identified by the two eyewitnesses. Nevertheless, Tony’s trial lawyers never presented this evidence to the jury.

It is likely that the El Paso police learned in the course of their investigation that Victor, not Tony, murdered Armando Murillo. However, by the time they learned this, the Murillo sisters had already identified Tony as the assailant. Apparently worried about their ability to convict someone as the killer, the police concealed this evidence.

The evidence of official suppression of evidence began to be revealed when Tony’s federal court lawyers were conducting new investigation in El Paso in 2002. By chance, they learned the following in a conversation with the court reporter from Tony’s trial: In 1992 or 1993, the court reporter who transcribed Tony’s trial was engaged by several El Paso police officers in a discussion about Tony’s case. The trial apparently had just occurred, because the officers were expressing their surprise that Mr. Ford had been convicted. They explained to Mr. Thomas that they were surprised, “because the word on the street was that another individual, Victor Belton, did the shooting.” The court reporter could not remember who these officers were.

Thereafter, Tony’s current lawyers found a man from El Paso who had known Victor. He recounted an incident at a party a year after the murder of Armando Murillo, in which he and another person were talking with Victor. During the conversation, Victor told them that he had gotten away with a murder.

In further investigation at this same time, Tony’s lawyers talked with the boyfriend of Myra Murillo. She told her boyfriend after she began to recover from her gunshot wound that there were three people involved in the break-in – one of whom a stayed outside.

Given the common knowledge among the El Paso police that the information “on the street” was that Victor Belton was the killer, it is virtually inconceivable that the police did not have this information from Ms. Murillo and did not have information from individuals who had heard Victor Belton admit what he had done.

One other fact not known to the police that confirms Victor’s involvement was uncovered by Tony’s lawyers in 2002. A friend of Tony acquainted with Victor and Van Belton was in the El Paso jail in December, 1991, when Van and Tony were arrested. Shortly thereafter this man was contacted by Van. This man explained:

He [(Van Belton)] asked me to finger Tony Ford for the murder. He wanted me to tell the police that Ford admitted to him that he was involved. I told Belton that I couldn’t do this because it wasn’t true.

Based on all this information, Tony’s federal habeas lawyers asked the federal court in El Paso to require the El Paso police and prosecutors to turn over all their non-public investigation files concerning Murillo’s murder to the court so that the truth could be determined about the police department’s knowledge of Victor’s role in the murder. The court turned down Tony’s request.

In spite of the troubling facts pointing clearly to

Tony Ford’s wrongful conviction, the federal district court

in El Paso denied his habeas petition without ever holding a hearing.

As indefensible as that decision was under the circumstances of his

case, the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit affirmed

it on June 22, 2005. The U.S. Supreme Court is expected to announce in

early January 2006 their decision on whether they will grant

Tony’s writ of certiorari.

Eight days before Tony’s scheduled December 7, 2005,

execution, State District Judge William Moody issued a stay until March

14, 2006. The stay was issued so that DNA testing can be performed on

the clothing Victor was wearing at the time he was arrested for

assaulting the police who came to arrest his brother Van, who was

identified by the Murillo daughters. The clothes Victor was wearing,

including his shoes, have been stored as evidence for 14 years. It is

known his shirt and pants had visible bloodstains on them. Those

clothes have never been tested for whether the blood on them matches

one or more of the Murillo family. If it does, then it will be

conclusive proof that Victor was the shooter – and that Tony

is innocent. Judge Moody, who presided over Tony’s trial in

1991, also authorized funding for a defense forensic expert to provide

independent input for the DNA testing that by state law must be

conducted by the Texas State Crime Lab.

* Richard Burr is one of Tony Ford’s attorneys. His office is in Houston, Texas.