Bill Heirens Asks For Help So He Won't Die In Prison For Another's Crime

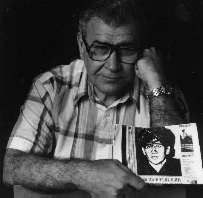

William Heirens, 53 of his 71 years in prison for a crime he didn't commit.

By Dolores Kennedy

(Editor: Clara A. Thomas Boggs)

Published in Justice:Denied, Vol. 1, Issue 10

William Heirens has been incarcerated in Illinois prisons for 53 years for crimes he did not commit. At the time of his conviction he was a 17-year-old student at the University of Chicago. On November 15, 1999, he turned 71. At an age before most of us marry, our first child is born or we enroll in college, Bill Heirens was sent to prison and was there while most of us pursued careers, raised our children, then watched them graduate. He is still there as many of us become grandparents, plan our pensions and begin to reflect back on our life experiences. A lifetime of memories lost, limited to the confines of prison, a lifetime for crimes he did not commit. How could this happen? Read on.

In 1946, Bill Heirens was in his sophomore year at the University of Chicago. The city was celebrating the return of the GIs from World War II, wartime rationing was subsiding, and the peacetime economy was reviving. Still, not all was peace. There were a number of unsolved murders making the headlines in the five daily Chicago newspapers. In June 1945, homemaker Josephine Ross was found stabbed to death in her apartment. In December 1945, ex-WAVE Frances Brown was shot to death. The words "For Heaven's sake, catch me before I kill more. I cannot control myself" were found scrawled in lipstick on her apartment wall. Most horrifying of all, six-year-old Suzanne Degnan was kidnapped from her home on the north side of Chicago and dismembered. Her body parts were found in the sewers of her north side neighborhood. An autopsy later revealed that the child had been strangled. The only clue to this crime was a ransom note asking for $20,000.

The Degnan crime shocked the nation. The public's fear and outrage was reflected in newspaper headlines screaming for the arrest of Suzanne Degnan's killer. The media throughout the United States and abroad carried the story. Police noted that it was a professional dismemberment and suspected a butcher or medically trained person. They followed hundreds of leads, but could not solve the crime.

Months passed without resolution. Parents, fearing for their children's lives, kept them indoors and escorted them to and from school. Daily, the newspapers mocked the police for failing to catch the killer.

In June 1946, six months after the Degnan crime, Bill Heirens was arrested on Chicago's north side in the act of attempted burglary. He was taken into police custody and interrogated for six days without counsel. During that time, he was accused of committing several unsolved murders, including the murder of Suzanne Degnan. The state's attorney illegally authorized an injection of sodium pentothal to "...get the truth out of him." Bill was given two lie detector tests. Under incredible pressure, he maintained his innocence.

While Bill was recovering from injuries inflicted by the police during his arrest, his defense counsel were summoned to the prosecutor's office where they were told that if Bill would confess to the Degnan, Brown and Ross murders, the State would assure them there would be no death penalty. His attorneys were told that their client would go to prison for life on the burglary charges alone. The lawyers decided to cooperate with the prosecution to obtain a confession.

Evidence of Bill's guilt began to appear. Police reported that the message on the Brown bedroom wall matched known samples of Heirens' writing. Handwriting on the Degnan ransom note was also a match. Hidden indentations on the ransom note tied Bill to the Degnan crime. A bloody fingerprint on the doorjamb of the Brown apartment was Bill's. The face of the Degnan note bore Bill's little fingerprint. There was no evidence in the Ross case, but the authorities thought it likely that the same person killed Brown and Ross. Therefore, they felt that Bill should be guilty of this crime as well.

In the middle of July, the Chicago Tribune published a front page headline story indicating that Bill had confessed to the crimes. They gave lurid details. This purely fabricated article was picked up by the remaining four daily Chicago papers and the news services. It was apparent to Bill that a fair trial would be impossible. Urged by his lawyers to accept the plea bargain, he confessed to all three murders to avoid certain death in the State's electric chair. In 1946, there was no appeals process. Within weeks, Bill Heirens would have been dead. From that standpoint, his plea bargain was completely understandable. Ten weeks after his arrest, during which the Chicago papers headlined the Heirens case 157 times, Bill Heirens began serving three life sentences.

For the next 40 years, Bill litigated his case in the hope of finally obtaining a fair trial. Because of the politics of the case and his confession, he failed. During all those years, no one looked at the underlying facts of this case. No one studied the evidence that had forced him into a confession. No one analyzed the events of 1946 in order to understand why Bill Heirens went to prison.

In 1987, Dolores Kennedy, social activist and author of, "William Heirens: His Day in Court," began to research the case against Bill Heirens. In 1994, she formed a justice team, headed by Jed Stone, a Chicago criminal defense lawyer, and they assembled psychiatrists, lawyers, handwriting analysts, fingerprint experts, professors and concerned citizens. The result of their research is staggering.

- The handwriting on the ransom note was not the writing of Bill Heirens

- The lipstick message on the wall was not Heirens' writing

- The lipstick message and ransom note were written by different people

- FBI reports stated that there was no hidden indentation writing on the note

- The "bloody" fingerprint from the Brown apartment was a "rolled" fingerprint, apparently lifted from a fingerprint card, and not the latent print the prosecutors had described

- The fingerprint on the "face" of the Degnan note was really on the back of the note, making this evidence fraudulent

- Results of the lie detector tests showed Bill to be an innocent man

Research also uncovered the existence of Richard Thomas, who confessed to the Degnan crime from his jail cell in Phoenix, Arizona shortly before Bill was arrested. Thomas was waiting to be sentenced for molesting his daughter. The Chicago police were summoned, but quickly lost interest in Thomas when the state attorney for Chicago announced that Bill was the killer. The justice team discovered that:

- Handwriting experts identified Thomas as the author of the ransom note

- Thomas lived in Chicago when Suzanne Degnan was killed and "hung out" at a car agency near her home

- Suzanne's arms were discovered in a sewer directly across from that same car agency

- Thomas was a male nurse who molested two of his three children

- Several years prior to the Degnan crime, he had been arrested for attempted kidnapping and extortion. Portions of the extortion letter have wording similar to that on the ransom note

- He was a petty burglar who was arrested on numerous occasions

The key to the 1946 prosecution was Bill's confession. The justice team compared the known facts of each murder to the versions Bill told to save his life. Careful analysis shows that Bill was simply wrong about facts, locations and events.

A review of all the evidence in this case leads to one conclusion. In 1946, Bill's lawyers failed to investigate, failed to challenge, failed to defend. In fact, Bill's lawyers have stated that they did not defend their client, only tried to keep him from a certain death in the electric chair. The Supreme Court excused this by saying that since counsel was hired, rather than appointed, it was Heirens' fault that they didn't serve his interests.

In 1953, the Illinois Supreme Court, after reviewing the facts, declared:

"Of course the search of petitioner's living quarters, the incessant and prolonged questioning of petitioner while he was confined to a hospital bed, and the unauthorized use of sodium pentothal and a lie detector, were flagrant violations of his rights. Such conduct on the part of law enforcement officials deserves the severest condemnation..."

The Court went on to say that since the case was settled on a plea bargain, the violations were not responsible for the conviction.

In 1968, Justice Luther Swygert of the United States Court of Appeals said, "The case presents the picture of a public prosecutor and defense counsel, if not indeed the trial judge, buckling under the pressure of a hysterical and sensation-seeking press bent upon obtaining retribution for a horrendous act. The state's attorney and defense counsel usurped the judicial function, complying with a community scheme inspired by the press to convict the defendant without his day in court."

In 1973, Illinois adopted the Unified Code of Corrections that changed Illinois penal laws. Under its provisions, Heirens' consecutive sentences were aggregated into one sentence. Illinois put into effect three specific criteria for parole: Is the prisoner capable of becoming a law abiding citizen, does the prison record warrant parole, and newly added parole should be denied if the release would "deprecate the seriousness of the offense or promote disrespect for the law." Retroactively applying the new paroling criterion effectively prevents pre-1973 prisoners from being paroled. If it were not for this retroactive application, Bill could have been paroled as early as 1984.

In 1995, a clemency hearing was held in Chicago at which the Illinois Prisoner Review Board had an opportunity to hear the expert witnesses and view the evidence used to force Bill's confession. Governor Edgar denied clemency to him more than three years later. In 1998, that same Review Board gave Bill a three-year set so they did not have to hear his case again until 2001. In 2001, Bill will be observing his 73rd birthday.

Though Bill has suffered one injustice after another, he has not allowed it to destroy his hopes or in any way define him. During Bill's long years of incarceration, he has worked hard to improve himself and the lives of those around him. Through correspondence courses, he accumulated 197 credit hours, becoming the first Illinois inmate to earn a Bachelor of Arts degree. At Stateville, he was employed by the prison garment industry, spending 10 years overseeing production. He learned television and radio repair and, when he was transferred to the honor farm at Stateville, he set up a repair shop on the grounds. Eventually Bill taught his skills to other inmates. Bill also assisted in developing many educational programs, counseled inmates who were interested in earning their GEDs, taught math courses, and worked in the law library at Vienna Correctional Center, helping countless inmates prepare legal documents and advising them of the possibilities available to them.

When he first entered the system, Bill began to develop his skills as an artist -- initially using colored ink and eventually transferring to watercolor. His paintings won many blue ribbons at Stateville art shows and continue to be in constant demand.

Until recently, Bill served as secretary to the Catholic priest at Vienna Correctional Center and continued his legal work for those he felt he could help. Realizing that he is living in a computerized world, Bill enrolled in computer classes at the prison. Last year, Bill asked for and received a transfer to Dixon Correctional Center, where he currently works in the business office. The victim of diabetes, he now makes frequent trips to the infirmary where he is often hospitalized for circulatory problems.

A lifetime of achievement in prison has brought the following accolades from the same parole board which refuses to release him: "You have done beautiful things," "I have never seen so much accomplishment" and, "I think you are a good example of what rehabilitation is all about."

The continued incarceration of Bill Heirens is a condemnation of our criminal justice system. An unpopular crime, a frenzied press, an anxious public, a zealous state's attorney, a pressured defense counsel, unconcerned courts, politicians seeking a "tough on crime" status, and a cowardly review board. These are the ingredients that have kept an incredible -- and innocent -- man in prison for more than half a century.

Please visit Bill's Wikipedia web site: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Heirens. If you would like to help, please contact the governor asking for the release of William Heirens. You may e-mail the Illinois Governor at governor@state.il.us.

Bill's only hope for a timely release is to ask the governor to commute his sentence to time served. Bill has already served many years more than most convicted of the same crime and remains in prison solely because he refuses to admit guilt. The evidence against him has proved to be fictitious or planted. The only standing evidence is a confession full of gaps and inconsistencies given under the threat of certain death. The false confession that saved his life has kept him in prison while his innocence has long been proven, but has been brushed aside by the court system.

Requests for Bill's release are especially important at this time. In February, his advocates will file a clemency petition, with a hearing scheduled for early April. Once again the entire review board will hear about Bill's innocence. Once again they will hear about his outstanding prison record. With no concern for justice, their recommendation to the governor will be based solely on public opinion. If they can be convinced that the majority of the public favors Bill's release, they will act on it. Nothing less will suffice. If you care to e-mail your concerns to Dolores Kennedy (see e-mail address below), your comments will be attached to the clemency petition. No one can give back the years Bill has lost, but you can help prevent Bill from losing more of the precious time he has left, and fulfill the hope that Bill has kept alive for 53 years.

Please write to Bill Heirens:

Mr. William Heirens, #C-06103

P.O. Box 1200

Dixon, IL 61021

Contact: Dolores Kennedy -- DeeKay925@aol.com